Théâtre Capitol (Montréal)

Joyau disparu de la rue Sainte-Catherine, le Théâtre Capitol (1921–1973) fut l’un des palais de cinéma les plus somptueux de Montréal, incarnant l’âge d’or du divertissement urbain avant l’arrivée de la télévision. Construit pour Famous Players par l’architecte new-yorkais Thomas Lamb, il a successivement accueilli cinéma, vaudeville, musique, danse et concerts rock, avant d’être démoli en 1973 pour faire place à un complexe de bureaux.[1][2][3][7][33]

1 — Présentation & contexte

Dans le passé, avant l'arrivée de la télévision, les gens allaient au cinéma. Ils y allaient souvent, une fois par semaine ou plus, et ne s'asseyaient pas dans des salles de cinéma rectangulaires comme aujourd'hui. Ils s'asseyaient dans de grands théâtres opulents avec des noms comme Loews, Palace ou Capitol, qui dégageaient une vie et une aura propres et faisaient presque partie du spectacle autant que l'aventure romantique à l'écran.[1][2]

Mais ensuite est arrivée la télévision, et les gens ont découvert qu'ils pouvaient rester chez eux et regarder gratuitement ce qu'ils devaient auparavant payer 0,25 $ ou 0,50 $. Les grands théâtres à Montréal, ainsi que dans toutes les autres villes d'Amérique du Nord, se sont retrouvés gravement sous-utilisés — 100 personnes un vendredi soir dans un théâtre conçu pour 2 000. Ainsi, au cours des années 1960 et 1970, les grands théâtres ont commencé à disparaître. Certains ont été divisés et sont devenus des complexes de salles de cinéma rectangulaires. D'autres ont été reconvertis en salles de concert. Mais la plupart, étant situés au centre-ville sur des terrains très prisés, ont été détruits et réduits en décombres et poussière comme ce fut le cas pour le Théâtre Capitol en 1973, l’un des plus grands théâtres opulents de Montréal.[1][2]

2 — Histoire & inauguration

Le Théâtre Capitol, situé sur la rue Sainte-Catherine Ouest, entre McGill College et Mansfield, était une véritable merveille de l'architecture moderne. Construit en 1921 pour Famous Players par la société Atlas et l’architecte new-yorkais Thomas Lamb, le Capitol était l'un des théâtres les plus luxueux et richement décorés de Montréal à l'époque. On y a présenté du cinéma, du vaudeville, de la musique et de la danse. Sa nécrologie le qualifiait de « plus bel exemple de l'opulence des palais de cinéma des années 1920 à Montréal ». [3][4][5][6][7][8]

Le critique de cinéma Dane Lanken, du Montreal Gazette, qualifiait le Capitol comme l'un des plus imposants théâtres jamais bâtis dans la ville : « Le Capitol était le plus vaste, le plus spectaculaire et presque le plus grand [le Loews ayant été le plus grand]. De nos jours, il est rare de se retrouver dans un cinéma avec 50 pieds d'espace au-dessus de sa tête, mais c'était assurément le cas au Capitol. »[9]

Érigé au coût de 1 million de dollars (soit environ 16 millions de dollars en valeur de 2024), il comptait 2 500 sièges et se distinguait par un plafond lumineux exceptionnel. À l’intérieur, le marbre abondait. La section musicale du théâtre incluait un orchestre de 27 musiciens dirigé par M. John Arthur et des orgues puissants, dont l'installation avait coûté 54 000 $ (soit environ 858 000 $ en 2024). À l'époque, Montréal comptait quatre théâtres de cette envergure : le St-Denis, l’Impérial, le Loews et le Capitol.[3][4][5][10]

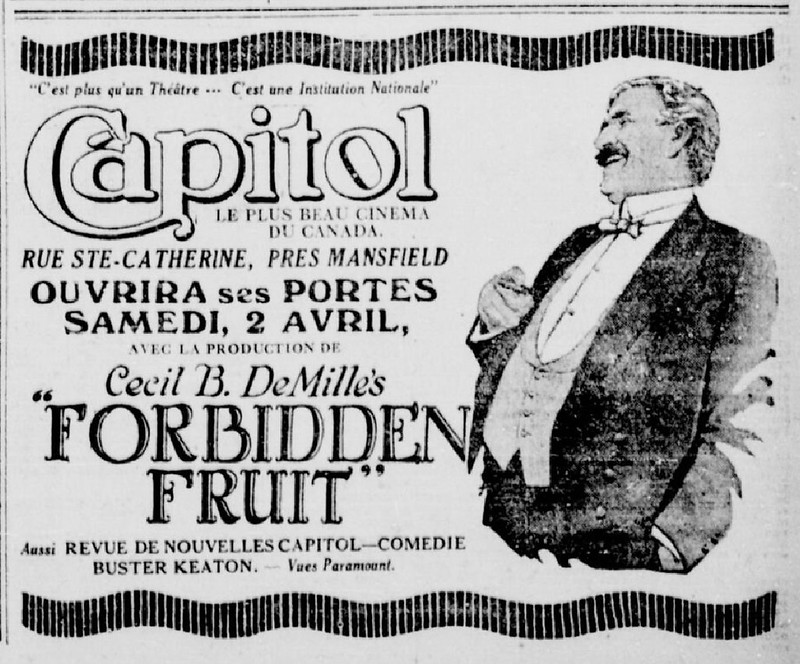

Plus de 3 000 invitations ont été envoyées pour l’inauguration du Capitol le 2 avril 1921. Devant un public sélect, un programme varié a été présenté, comprenant des vues animées, de la musique, des extraits d’opéras, de la pantomime et des danses. Léo-Ernest Ouimet, le fondateur du premier cinéma au Canada (le Ouimetoscope) et président-directeur général de Specialty Film Import Ltd, a prononcé le discours d'ouverture. Le film projeté était Forbidden Fruit, un film muet américain réalisé par Cecil B. DeMille, accompagné de l’orchestre du Capitol et suivi de bobines récentes sur le Vieux-Québec. Pour l'occasion, les actrices vedettes américaines Elsie Ferguson, Hope Hampton et Alice Brady étaient présentes, offrant une soirée digne de Broadway sous la bannière de Famous Players.[3][4][10]

Avant le début de la représentation, le public a eu l'occasion de visiter l'ensemble du théâtre, guidé par les directeurs qui leur ont fait découvrir tous les recoins de l’établissement. De nombreuses personnalités furent ensuite reçues au Ritz-Carlton, au St-James Club, au Hunt’s Club et au cabaret Ciro’s, où un repas fut servi suivi de danse.[4][5]

Pendant plus de cinquante ans, le Capitol, un cinéma bilingue, a apporté la magie d'Hollywood et des grands noms du divertissement sur scène, contribuant à l'image de la rue Sainte-Catherine comme centre de divertissement majeur à Montréal.[11][12]

3 — Architecture & caractéristiques

Le Capitol était souvent cité comme l’un des plus beaux palaces de cinéma du pays. Sa façade et son hall d’entrée donnaient le ton d’un luxe assumé : marbre, balustrades élégantes, sculptures, luminaires imposants, plafond lumineux spectaculaire et salle d’une hauteur impressionnante, créant l’effet d’une nef de cathédrale dédiée au spectacle.[3][4][7][9]

Son volume intérieur, avec quelque 2 500 sièges, rappelait le Loews, autre géant de la rue Sainte-Catherine. L’espace au-dessus des têtes du public, évoqué par Dane Lanken (50 pieds ou plus), participait à l’effet de grandeur. Un orchestre de 27 musiciens et un orgue de cinéma sophistiqué assuraient la dimension sonore lors des projections muettes et même par la suite lors d’événements particuliers.[3][4][5][9][10]

Le Capitol était ainsi représentatif de l’architecture des grands « movie palaces » des années 1920 : un théâtre suffisamment polyvalent pour accueillir films, vaudeville, opérette, danse, concerts, et plus tard, rock et pop, tout en maintenant une identité visuelle très forte, marquée par l’opulence et la monumentalité.[1][3][8]

4 — Événements marquants & vie culturelle

4.1 — Hold-up de 1934

Le 18 avril 1934, un hold-up a eu lieu au Théâtre Capitol. Moins de cinq minutes se sont écoulées entre le moment du braquage audacieux et l'arrestation du suspect par le sergent détective. Avant le hold-up, une somme de 800 $ (soit environ 17 803 $ en 2024) avait été transférée dans le coffre du Capitol. Dix minutes plus tard, le suspect, Elphèse Montpetit, s’est présenté avec un sac dans une main et un revolver dans l’autre, demandant à la caissière : « Remplissez le sac ! ». Mlle Evelyn Bernier, la caissière, a mis l'argent en sa possession dans le sac.[13]

Le voleur, nerveux, a alors rangé son revolver et son sac dans ses poches avant de fuir. Une voiture de patrouille, remarquant une petite foule autour du guichet, a alerté le sergent, qui a commencé à chercher le suspect. Ayant reçu une description vague, le sergent a arrêté Montpetit sur la rue Metcalfe. Ce dernier était en possession dans son sac de seulement 22 $ de l’argent volé (soit environ 484 $ en 2024) et de son revolver rouillé et déchargé. Montpetit, âgé de 29 ans, était marié et père de trois enfants. Il a purgé une peine de cinq mois de prison.[13][14]

4.2 — Hold-up de 1951

Le 6 août 1951, un autre hold-up a eu lieu au Capitol. Un gentleman blond moustachu a dérobé 1 920 $ (soit environ 22 093 $ en 2024) après être entré dans le bureau du directeur en passant derrière le portier et la caissière. Le directeur Bill O’Loghlin a informé les détectives que le voleur avait attendu un certain temps dans le hall avant de passer à l’action.[15]

4.3 — Hold-up de mai 1953

Le 6 mai 1953, à l’heure de pointe, deux jeunes voleurs ont braqué le Capitol et se sont enfuis avec 95 $ (soit environ 1 076 $ en 2024). Il s’agissait du deuxième vol pour la caissière Madeleine Leathead. Peu avant cinq heures, les deux individus se sont approchés du guichet. L’un d’eux a remis une note à Mlle Leathead indiquant : « C’est un hold-up ! ». Le directeur Bill O’Loghlin a expliqué que la faible somme volée était due à la tranquillité habituelle d’un mercredi soir.[16]

4.4 — Hold-up de juillet 1953

Le 15 juillet 1953, un hold-up en plein jour a eu lieu au Capitol, se concluant par l'arrestation du voleur à la Gare Centrale. Le vol a été perpétré par un jeune homme en état de nervosité remarquable, qui tentait de s'enfuir avec 34 $ (soit environ 385 $ en 2024) volés au Capitol lorsqu'il a été capturé après une poursuite et des échanges de tirs.[17]

« J'ai vu une foule poursuivre un jeune homme et j'ai entendu un policier crier "Arrêtez-le !", alors je l'ai arrêté », a déclaré Henry Abbott, vendeur d'assurances. Le hold-up s'est produit lorsque le jeune homme s'est présenté au guichet du théâtre, a remis une note à la caissière, et a reçu 34 $. Interrogé sur les raisons pour lesquelles plusieurs hold-ups se produisaient en plein jour et en centre-ville où la circulation est dense, le capitaine-détective Roméo Longpré a expliqué que les bandits croyaient pouvoir se fondre dans la foule pour échapper à la capture.[17]

4.5 — The Beatles : A Hard Day’s Night, 1964

Environ 1 000 adolescents encerclaient un quadrilatère du centre-ville de Montréal attendant qu’on ouvre les portes du Théâtre Capitol qui offrait la première représentation du film A Hard Day’s Night des Beatles, le 7 août 1964.[18][19]

Le film commençait à 10 h du matin, mais la file d'attente avait commencé à se former tard la veille. La direction du Capitol avait engagé plusieurs patrouilleurs d'agences privées pour superviser la file d'attente, ainsi qu'une douzaine de policiers montréalais. Des milliers d'adolescents enthousiastes attendaient l'ouverture des portes pour voir le film des Beatles. C'était la plus bruyante et l'une des plus grandes foules dont se souvienne le directeur général du Capitol en 1964, Phil Maurice (ancien gérant du cabaret Chez Maurice). Le Théâtre Capitol était plein à capacité — 2 700 sièges — lorsque le film a commencé.[18][20]

Le lieutenant de police Jean Lavigne a déclaré : « Plus de 50 jeunes se sont joints à la file pendant la nuit. À 8 h 30, les milliers de jeunes en délire s'étendaient de l'entrée du théâtre jusqu'à l'avenue McGill College, puis jusqu'à la rue Cathcart, à l'ouest jusqu'à la rue Mansfield, puis remontaient et se dirigeaient à l'est le long de la rue Sainte-Catherine. » Il ajouta : « Je ne suis pas en position de commenter sur les Beatles, mais ces jeunes sont corrects ! ». Aucun incident ne fut à déplorer.[20]

4.6 — Van Morrison & Edgar Winter, 1971

En 1971, Famous Players a mis son Théâtre Capitol à la disposition des collèges Dawson et Vanier pour des concerts de rock et de pop dans le cadre de leurs festivals d'hiver.[21][22][23][24][25]

Le 22 février 1971, le chanteur Van Morrison, bien connu pour son hit « Brown Eyed Girl », a donné un concert au Capitol dans le cadre du festival d’hiver du collège Dawson. Le spectacle a commencé avec 45 minutes de retard, réduisant ainsi le temps de performance de Morrison. Malheureusement, la sonorisation du Capitol était défaillante : dès le début, le système audio a rencontré des problèmes, et malgré les efforts pour corriger la situation, le son était déformé par la distorsion, mal équilibré entre les instruments, et affecté par l’acoustique particulière de la salle. Morrison a fait preuve de beaucoup de patience, mais la voix était complètement altérée et l’orchestre désordonné. Bien que le spectacle ait été accompagné d’un light show réussi malgré ses moyens modestes, les éclairages ont été critiqués par un journaliste de La Presse comme étant « les plus laids que j’aie vus récemment ». De nombreux spectateurs ont quitté le spectacle déçus.[21][22]

Le lendemain du spectacle de Van Morrison, c'était au tour du collège Vanier d'organiser son festival d'hiver au Théâtre Capitol, et malgré les nombreux défis rencontrés, ils ont réussi à le mener à bien. Un trio de Floride nommé Tin House a ouvert le spectacle, affrontant un son presque impossible à délivrer. Ensuite sont arrivés Edgar Winter et son groupe White Trash. Miraculeusement, le système de sonorisation a subi une transformation complète. Le son était clair comme du cristal et parfaitement équilibré. Pour plusieurs critiques, c'était le concert rock de l'année.[23][24][25]

4.7 — Le Capitol, palais du rock en 1973

En 1973, il faut ajouter au Forum, à l’Université de Montréal (CEPSUM) et à l’Aréna Paul-Sauvé le nom du Théâtre Capitol comme lieu important de concerts rock. En avril 1973, l’impresario Donald K. Donald (Don Tarlton) annonce avoir conclu un accord avec Famous Players pour louer le théâtre historique de la rue Sainte-Catherine deux fois par mois pour ses productions.[26]

Le premier spectacle au Capitol organisé par Donald K. Donald est celui du groupe de rock le plus populaire d’Angleterre à l’époque, Slade, le 24 avril 1973. « Je louais des salles auprès de United Theatres à travers le Canada », explique Tarlton. « Les installations scéniques au Capitol étaient excellentes. » Tarlton précise que le Capitol restait un cinéma, sauf les soirs de concert. Le 24 mai 1973, DKD présente Seals & Crofts, qui ont alors un single populaire intitulé « Summer Breeze ». Le 11 juin 1973, Tarlton prévoit présenter Dr. Hook au Capitol (le spectacle sera finalement annulé). Cette annonce survenait après l’arrivée en ville d’un nouveau promoteur rock, Martin Haber, basé à New York, qui commence à programmer des spectacles et amène B.B. King et John Lee Hooker au Capitol le 10 mai 1973.[26]

4.8 — Lou Reed au Capitol, 1973

Cela n’arrivait pas très souvent, mais une nuit par an, l'underground de Montréal refaisait surface. Il a montré le bout de son nez et une partie de son corps lors du concert de Lou Reed au Capitol le 17 mai 1973. Reed était la figure emblématique de l'underground new-yorkais, qui, selon le chroniqueur Bill Mann, était généralement en avance d'un an ou deux sur celui des autres villes. Cependant, l’avant-garde montréalaise n’avait pas à rougir, compte tenu de certains personnages présents ce soir-là.[27]

Un homme est venu déguisé en Mr. Peanut, un autre en bouteille de ketchup Heinz, et un couple est arrivé en baignoire et douche, tandis que la scène gay a pris un peu d'air frais. Lou Reed est monté sur scène en cuir. Sa superbe interprétation de « Heroin » a probablement été le point culminant du spectacle. L'atmosphère d'unité était palpable, et le son ainsi que les éclairages étaient excellents. Le Théâtre Capitol s'est approché de l'expérience immersive totale.[27]

Lorsque l’on parle de l’underground d’une ville, on ne parle pas de la scène de drogue, mais d’un mouvement en avance sur son temps, environ vingt ans devant la société en général, centré sur les arts. La chanson que les gens étaient venus écouter était bien sûr « Walk On The Wild Side », la première fois que l'underground faisait surface sur les ondes des radios mainstream. « I said, Hey Babe, take a walk on the wild side », chantait Reed dans une provocation ouverte envers les codes hétérosexuels. « And the coloured girls go, Doo, do-doo, do-doo, do-do-doo », et le public chantait en chœur. C'était une véritable alchimie.[27]

4.9 — King Crimson & Octobre, 1973

Le 20 septembre 1973, le concert de King Crimson au Capitol se tient à guichets fermés. La soirée « King Crimson–Octobre » attire un public conquis, et le Capitol est à son meilleur — un vénérable palais du rock. King Crimson, groupe britannique de rock progressif, est alors l’un des plus importants du genre, et leur public à Montréal est nombreux.[30][31]

Le groupe québécois Octobre ouvre la soirée et « a presque volé la vedette » selon la critique, grâce à ses improvisations très réussies. « Quand on a fait la première partie de King Crimson au Capitol, le promoteur Donald K. Donald nous a donné 60 $ chacun », se rappelle Pierre Flynn. « Le directeur technique de King Crimson s’est mis à rire quand il nous a vus arriver avec notre p’tit équipement. Leur équipe nous a quand même bien traités, et on a eu un rappel. À la fin, les gars de King Crimson nous regardaient jouer, et le directeur technique nous levait son pouce. On avait gagné notre point. »[28][29][30][31]

Ce concert contribue à placer Octobre, et plus largement la scène rock québécoise, sur la carte d’un rock progressif en pleine expansion au début des années 1970.[28][29][30][31]

5 — Déclin, fermeture & démolition

En 1973, Famous Players indique que le Théâtre Capitol n’avait pas été rentable depuis au moins dix ans. L’entreprise décide donc de démolir le théâtre pour faire place à une tour de bureaux.[7]

Le 11 novembre 1973, 25 objets sont mis en vente aux enchères au Capitol : des vases chinois, des tableaux, des copies de grands maîtres, une statue en marbre d'une déesse grecque, des chandeliers et des lampes. Tout est à vendre. Même après l'enchère, il suffit de faire une offre pour obtenir des portes vitrées, des rampes ou tout ce qui est encore accroché aux murs. On vide le Capitol. Le lendemain, on coupe l'eau et on retire les bancs. Le week-end suivant, on commence la démolition de ce cinéma vieux de 52 ans.[32]

Tom Cleary, animateur de la soirée de ventes aux enchères, avait été placier au Capitol à l'âge de 17 ans, au moment de l'ouverture du cinéma en 1921. « J'étais payé 1 $ par soir. Ce n'était pas beaucoup, c'est vrai, mais je voyais tous les films et les spectacles gratuitement. » Les plus anciens cinémas de Montréal étaient conçus comme des salles de spectacles. Le Capitol, qui avait récemment accueilli Rory Gallagher, Chick Corea, Dr. John, John Mayall, Mireille Mathieu et d'autres artistes, servait de salle pour les tournées.[32]

« Les représentations commençaient à 13 heures à l'époque », se souvient Cleary. « Il y avait du vaudeville, de l'opérette, de la danse classique et des séances de cinéma muet. L'orchestre comptait 16 musiciens. Contrairement aux autres salles, le Capitol n'avait pas de piano pour accompagner les films, mais un organiste. »[32]

C'est dans un désordre total et une confusion complète qu'on dit adieu à une époque. Les hôtesses portent des robes à la mode des années 1920, les placiers des canotiers et des vestons rayés rouges et blancs. Le champagne coule à flots, et une jeune fille se baigne dans une baignoire remplie de champagne. « Le Capitol était le plus beau et le plus riche des théâtres de Montréal. Le seul autre théâtre presque aussi beau et riche ne devait ouvrir que six mois plus tard, il s'agissait de l'Allen, devenu le Palace. »[32]

Monsieur Cleary quitte le Capitol en 1926 avec une montre en cadeau de reconnaissance, qu'il possède toujours en 1973 au moment de la fermeture. Il devient ensuite assistant-gérant du Palace, revient au Capitol, puis part diriger les guichets de l'Orpheum. Tom Cleary terminera directeur de la publicité chez Famous Players avant de prendre sa retraite à 70 ans.[32]

Le dernier film projeté au Capitol est The Stone Killer mettant en vedette Charles Bronson. L'hypnotiseur Reveen donne le dernier spectacle.[32]

Les membres du public présents pour le dernier acte du Capitol ne sont pas satisfaits. Des huées éclatent lorsque la maquette de la future tour de bureaux qui doit remplacer le Théâtre Capitol est présentée sur scène. La soirée se termine par un dernier rideau et le chant de « Auld Lang Syne ». Peu de gens restent dans le théâtre. L’une des rares personnes restantes monte calmement sur scène et verse son verre de champagne sur la maquette du nouveau bâtiment de 23 étages.[7]

Le cinéma Capitol est démoli en décembre 1973, en même temps que le cinéma Pigalle (anciennement le Strand), ainsi que tous les immeubles entre McGill College et Metcalfe sur le versant sud de la rue Sainte-Catherine, à l'exception du restaurant Dunn's et du Cinéma de Paris.[32]

Le site est dégagé pour un projet polyvalent de 21 millions de dollars sur Sainte-Catherine, le Centre Capitol (aujourd’hui la Tour Rogers).[33]

6 — Chronologie rapide

- 1921 — Construction achevée et inauguration du Théâtre Capitol le 2 avril.[3][4][10]

- Années 1920–1930 — Âge d’or du cinéma muet, du vaudeville, de l’opérette et de la danse au Capitol.[3][4][8]

- 18 avril 1934 — Hold-up d’Elphèse Montpetit, arrêté quelques minutes après le vol.[13][14]

- 6 août 1951 — Vol de 1 920 $ par un « gentleman » moustachu.[15]

- 6 mai & 15 juillet 1953 — Deux nouveaux hold-ups, dont un poursuivi jusqu’à la Gare Centrale.[16][17]

- 7 août 1964 — Première de A Hard Day’s Night des Beatles devant une foule adolescente immense.[18][19][20]

- 22–23 février 1971 — Concerts de Van Morrison (sonorisation ratée) et d’Edgar Winter (concert encensé) dans le cadre de festivals collégiaux.[21][22][23][24][25]

- 10 mai 1973 — Concerts de B.B. King et John Lee Hooker au Capitol, sous la houlette de Martin Haber.[26]

- 17 mai 1973 — Lou Reed fait remonter l’underground montréalais à la surface avec un concert culte.[27]

- 24 avril 1973 — Slade en concert, premier événement produit par Donald K. Donald au Capitol.[26]

- 24 mai 1973 — Seals & Crofts jouent au Capitol.[26]

- 20 septembre 1973 — Concert de King Crimson avec Octobre en première partie, à guichets fermés.[28][29][30][31]

- 11 novembre 1973 — Vente aux enchères, dernier film (The Stone Killer) et dernier spectacle (Reveen) au Capitol.[32]

- Décembre 1973 — Démolition du Théâtre Capitol.[32][33]

7 — Notes & sources

- Grand old movie theatres on the brink of extinction, The Gazette, Dane Lanken, 25 février 1984.[1]

- How long can we keep our historic buildings?, The Gazette, 16 mars 1974.[2]

- L’inauguration d’un magnifique théâtre à Montréal, Le Panorama, 1921 v2 no7.[3]

- Le Capitol, Le Panorama, 1921, v2 no10.[4]

- Inauguration du Théâtre Capitol, La Patrie, 10 mars 1921.[5]

- Soviet film will have special soundtrack, The Gazette, 11 octobre 1988.[6]

- Loss of Montreal’s Capitol Theatre was a bitter pill for many, The Gazette, Linda Gyulai, 27 février 2015.[7]

- Vaudeville au théâtre Capitol, La Presse, 3 septembre 1927.[8]

- Opulence reeled in crowds, The Gazette, Linda Gyulai, 28 février 2015.[9]

- Capitol will open at 8 O’Clock TONIGHT: Cecil B. DeMille’s Forbidden Fruit, The Montreal Star, 2 avril 1921.[10]

- Right on target, The Montreal Star, Charles Lazarus, 22 novembre 1975.[11]

- Capitol, La Presse, 4 avril 1922.[12]

- Capitol theatre scene of hold-up, The Gazette, 19 avril 1934.[13]

- Leniency for bandit, The Gazette, 5 mai 1934.[14]

- Three holdups net 11,975$ fourth averted, The Montreal Star, 7 août 1951.[15]

- Un autre vol au Capitol, La Patrie, 7 mai 1953.[16]

- Arrestation d’un bandit suite à un hold-up au Capitol, La Patrie, 16 juillet 1953.[17]

- The Beatles in Montreal, The Gazette, Alan Hustak, 4 septembre 1994.[18]

- Le film des Beatles connaît le succès avant même d’être montré, Le Soleil, 8 août 1964.[19]

- Beatles fans mob heroes’ movie, The Montreal Star, William Wardwell, 6 août 1964.[20]

- Van Morrison au Capitol, Le Devoir, Jean Basile, 21 février 1971.[21]

- Van Morrison, pas de son pas de spectacle, La Presse, Yves Leclerc, 23 février 1971.[22]

- Edgar Winter’s rock group, merely heavy and gargantuan, The Montreal Star, Juan Rodriguez, 24 février 1971.[23]

- The rock concert of the year, The Gazette, Herbert Aronoff, 24 février 1971.[24]

- Edgar Winter très bon demi-spectacle, La Presse, Yves Leclerc, 24 février 1971.[25]

- DKD plans shows at the Capitol, The Gazette, Bill Mann, 10 avril 1973.[26]

- Lou Reed brings up the neighborhood, The Gazette, Bill Mann, 18 mai 1973.[27]

- Octobre à Musique Plus, Le Devoir, Sylvain Cormier, 28 novembre 1995.[28]

- At 51, Pierre Flynn is all alone and loving it, The Gazette, Juan Rodriguez, 11 mai 2006.[29]

- Interesting evening with King Crimson, The Gazette, Bill Mann, 21 septembre 1973.[30]

- King Crimson wears thin, The Montreal Star, Juan Rodriguez, 21 septembre 1973.[31]

- Le dernier soir des années folles au Théâtre Capitol, La Presse, Christiane Berthiaume, 12 novembre 1973.[32]

- No longer soft in head if you develop Montreal, The Montreal Star, 5 janvier 1974.[33]