Club 1234 (Montreal)

Opened on August 8, 1978 at 1234 de la Montagne Street, the Club 12-34 (often referred to as “twelve-thirty-four”) quickly established itself as one of downtown’s most spectacular discotheques at the height of the disco era. Housed in a former funeral chapel, the venue was transformed into a multi-level megaclub featuring ultra-modern sound and lighting systems, designed to accommodate up to 1,500 people. The press described 12-34 as a symbol of “high chic” and the high profits generated by Montreal’s disco boom. 1, 6, 17

1. Club 12-34 in Montreal nightlife history

In the late 1970s, Montreal underwent a major transformation of its nightlife. Disco was no longer just a musical genre: it became a total urban culture, combining music, fashion, light, architecture, and social performance. Discotheques evolved into show-spaces where lived experience mattered as much as the sounds on the speakers.

In this context, Club 12-34 emerged as one of downtown’s most ambitious venues. Its name—taken directly from its address—worked as an easy-to-remember mnemonic signature, helping build rapid notoriety among regulars, tourists, and cultural columnists.

The anglophone press, especially The Gazette, portrayed Montreal discotheques as places where chic and profitability reinforced one another. Within that landscape, 12-34 was cited as an example of a club capable of generating both heavy traffic and a prestigious nightlife image. 1

Disco as an urban phenomenon

In the late 1970s, disco reshaped Montreal’s nighttime geography. The Crescent, Peel, and de la Montagne areas concentrated bars, hotels, restaurants, and discotheques. These corridors became party arteries, where the circulation of crowds—tourists, conventions, young professionals— fueled a fast-growing entertainment economy.

Club 12-34 contributed to this urban reconfiguration by offering a large-capacity space, visually spectacular and able to host substantial crowds. It belonged to the lineage of major disco projects designed to impress as much through architecture as through atmosphere.

2. From funeral to festivity: architectural conversion

Before becoming one of downtown’s most spectacular discotheques, the building at 1234 de la Montagne Street housed a funeral chapel operated by Wray-Walton-Wray. Designed to accommodate ceremonial gatherings, such places often featured distinctive architecture: high volumes, open ceilings, broad central spaces, and smooth crowd circulation. 2

Converting a space of mourning into a discotheque reflected a broader late-1970s trend, as institutional and commercial buildings were repurposed for cultural and festive uses. In the case of Club 12-34, the conversion was especially spectacular: nearly $1 million was invested to adapt the existing architecture to the needs of disco culture. 4

The work aimed to create a multi-level megaclub capable of welcoming up to 1,500 people. Former ceremonial spaces were restructured to include:

- a large-capacity central dance floor,

- mezzanines and observation balconies,

- multiple bars distributed throughout the venue,

- a powerful sound system,

- lighting designed to create an immersive atmosphere.

The former funeral chapel thus became a space of collective celebration, where music, dance, and staging replaced rituals of mourning. This symbolic inversion—from ceremonial silence to disco frenzy—strengthened the spectacular aura of Club 12-34.

From sacred to profane

Turning a funeral chapel into a discotheque reflects a major cultural shift in the late 20th century. Places once associated with the sacred, death, and contemplation were reinvested by festive, bodily, nocturnal practices. Club 12-34 thus became a symbol of the passage from a culture of ritual to a culture of spectacle.

This architectural reconfiguration was not only functional. It also helped create a strong brand image: a monumental club, impressive for its size, décor, and atmosphere. The building itself became part of the experience, shaping the visual and memorial identity of 12-34.

Before the funeral home: a bourgeois residence (1859)

A heritage notice published in La Presse in 1985 notes that the building at 1234 de la Montagne Street was constructed in 1859 for David Wood, and later occupied by Sir Alexander Galt beginning in 1865.

The building was converted into a funeral home as early as 1902, which led to a façade alteration, including the construction of a new entrance with bay-window fenestration. The notice also mentions a balustrade and a mansard roof in red tile.

This earlier transformation confirms that the building’s funeral use belonged to a long history of conversions, well before it became a disco discotheque in the late 1970s. 31

3. From announcement to opening: the birth of Club 12-34 (June–August 1978)

Even before its official opening, Club 12-34 was framed in the press as a major project. A notice published in Montréal-matin in June 1978 states that the new discotheque “will take the name of its address: 12-34”. 17

The announced décor relied on a deliberate contrast between old and new: certain architectural elements of the chapel, notably the stained glass, were preserved and integrated into a contemporary layout. This “sacred / disco” aesthetic was conceived as a show-décor, designed to impress patrons from the moment they stepped inside. 17

A “phase one” 12-34

Montréal-matin also presented 12-34 as the starting point of a future large complex if the discotheque proved successful: a terrace, a restaurant, a brasserie, and even shops could be added. From the outset, 12-34 was thus conceived as a downtown nightlife commercial hub. 17

The project’s launch is associated with Gary Chown, then 26, born in Ottawa and raised in Montreal. A history graduate of Bishop’s University (Lennoxville) and a former Alouettes draft pick in 1974, Chown embodied the figure of the young promoter involved in the emerging disco scene. 17

The project also rested on a team of partners: Michael Bookalam, François Cobetto, Sol Zucherman, and Sharon Weis are identified as co-owners, while Brian Weiss served as the club’s manager. This structure reflects the collective investment model typical of late-1970s major disco clubs. 17, 23

Personal context for the promoters (summer 1978)

In late June 1978—only weeks before Club 12-34 opened—the Bookalam family was struck by tragedy. Sharon Bookalam (née Weiss), sister of Michael Bookalam, died accidentally at age 25.

Reported in La Presse obituaries, this detail reminds us that the club’s launch unfolded within a human context shaped by personal events, alongside the project’s commercial and cultural ambitions. 37

The official opening of Club 12-34 took place on August 8, 1978, a date confirmed by period promotional announcements and press coverage. The event was framed as the arrival of a new mega-discotheque downtown, designed to rival the most prestigious venues on Montreal’s disco scene. 3

From its first weeks, 12-34 attracted a large and varied clientele: young professionals, tourists, dance enthusiasts, and nightlife regulars. The spectacular nature of the venue—monumental architecture, immersive lighting, powerful sound— created a strong novelty effect that fueled word of mouth.

Early nights were described as intensely staged experiences: disco music structured the evening, while lighting effects, reflections, and crowd circulation turned the dance floor into a true social theatre.

“Disco isn’t only music—it’s a complete staging of the body, light, and the gaze.”

Club 12-34 also leaned on the event dimension of nightlife: weekend openings, themed nights, and extended hours helped build its image as a must-go destination for anyone seeking the “real” Montreal disco experience.

The novelty effect

In disco culture, the opening of a new club is an event in itself. The first weeks establish the venue’s reputation: sound quality, atmosphere, clientele, service flow, and perceived prestige. Club 12-34 benefited fully from this novelty effect, amplified by the scale of investment and the building’s unusual character.

The opening of 12-34 came at a moment when Montreal was often described as electrified by disco. Columns spoke of an intense nightlife in which discotheques became spaces of identity performance, as much as places for dance and socializing.

Before 12-34: the founders in Montreal’s scene (1977)

Before the creation of Club 12-34, several future co-owners were already active in Montreal nightlife. A Montreal Star article from June 1977 presents Michael Bookalam, François Cobetto, and Andres Villarruel as the team behind the club Bogart’s, located at 1215 de Maisonneuve West.

The three men, then aged 25 to 31, had previously worked at Don Juan and were deeply involved in Bogart’s management, programming, and ambience—an establishment inspired by the film-world aesthetic of Humphrey Bogart.

This experience suggests the 12-34 promoters already had first-hand knowledge of the club business before launching their more ambitious project at 1234 de la Montagne Street in 1978. 36

3.1 An early shock: violence and temporary closure (September 1978)

Only weeks after opening, Club 12-34 was struck by a violent incident that abruptly marked the venue’s early history. On September 14, 1978, Montréal-matin reported an attempted murder inside the discotheque at 1234 de la Montagne Street, leading to an immediate closure. 18

The victim, Bob Weiss, 25, a bartender at the establishment, was shot in the liver and rushed to the Montreal General Hospital, where he was listed in intensive care. The incident occurred shortly after 3 a.m., while about fifty patrons were still inside the club. 18

According to unconfirmed information reported by the newspaper, the shooting may have been triggered by a refusal to serve alcohol after closing time, prompting a customer to pull out a firearm and shoot toward the bartender. 18

The police response was substantial: about twenty patrol cars were dispatched, several patrons were taken to Station 10 for questioning, and charges were expected in related matters. 18

The article also notes the psychological impact: three or four young women were hospitalized for nervous shock, after screaming for several minutes following the gunshot. 18

4. Size, capacity, and the megaclub economy

From the outset, the Club 12-34 was designed as a “large-format” discotheque, built to absorb crowds and monetize a disco experience rooted in staging, the mass effect, and consumption. Figures cited in the press describe a venue that was outsized for downtown: a footprint ranging from about 15,000 to 20,000 sq. ft., capacity for up to 1,500 people, and layouts engineered to sustain extremely high traffic. 6, 7

This logic is typical of the late 1970s: the disco industry bets on spaces where dance becomes a central attraction, and where architecture is used to multiply viewpoints (mezzanines, balconies) and organize flows (entry lines, bars, circulation zones).

“High chic”: prestige and profit

Media discourse in 1978 often framed disco as a paradoxical economy: a culture of glamour (fashion, lighting, spectacle) that also aimed for high profits. In this model, a megaclub like the 12-34 did not simply sell music; it sold an experience and a social stage. 1

By 1979, Club 12-34 appeared regularly in Montreal’s society and fashion pages. Photo shoots, style columns, and elite social events were held at the venue, confirming its status as a prestige social space beyond its basic function as a nightclub. 19

International and local celebrities were frequently associated with evenings at the 12-34. These included film star Omar Sharif, Princess Caroline of Monaco, and Montreal Canadiens legend Guy Lafleur, whose fashionable presence— famously noted with a crocodile-skin bag—reinforced the club’s image as a chic jet-set destination. 21, 52

The 12-34 thus became more than a disco: it functioned as a media stage and a space of representation, regularly used by the press to illustrate disco culture, fashion, celebrity, and downtown social spectacle. 20

However, this image was not purely organic. An August 1979 investigation revealed that several nightlife columnists also worked as publicists or hosts for the very venues they covered, including Club 1234. This overlap between journalism, promotion, and nightlife marketing highlights how the club’s prestige was partly manufactured in print, not only earned on the dancefloor. 53

Montreal, “Disco City” (1979)

In the late 1970s, Montreal was widely portrayed in the anglophone press as a major international disco capital. A July 1979 article in The Gazette described the city’s nightlife as intense, crowded, and highly commercialized, with long lineups on Guy Street and Crescent Street, loud music, heavy drinking, and a booming entertainment economy.

The columnist emphasized how air-conditioned discotheques, massive sound systems, and spectacular lighting transformed downtown into a continuous party zone, where hundreds of patrons queued nightly to access the city’s most fashionable clubs.

Montreal was also presented as an internationally recognized disco hub, exporting artists, styles, and trends beyond Canada. Music producer and performer Gino Soccio was cited as an example of this success, with hit records, international sales, and strong media visibility.

This media narrative helps situate venues like Club 12-34 within a broader urban culture where nightlife, celebrity, consumption, and spectacle reshaped downtown Montreal’s identity at the height of the disco era. 50

5. Sound, light, and immersion: the nightclub as a machine

By 1978, the modern discotheque is often described as an audiovisual machine: powerful sound, “spectacular” lighting, reflective effects, haze, glossy surfaces, and the orchestration of the dancefloor. The 12-34 belongs to that generation of venues where technology becomes a marker of prestige — and a key differentiator. 1, 6

Sources from 1978–1979 emphasize how “speakers and lights” transformed the space, and the scale of investment required to reach that level of immersion. 4, 6, 22

« …it would be impossible to recognize the place today, so thoroughly have the speakers and lighting effects transformed the former funeral home. »

In the disco ecosystem, these kinds of systems produce a double effect: (1) dance as spectacle (a visible floor, crossed gazes, bodies staged), and (2) the crowd as attraction (the intensity of the place becomes proof of value).

In 1980, the Club 12-34 also stands out for the cost of admission. The Gazette reports that a $9 cover charge is required on Saturday nights — described as the highest in Canada at the time. Owner Sol Zuckerman explains that this price helps offset the cost of a four-colour laser system, presented as unique in the country. 24

In 1980, the Club 12-34 begins a notable aesthetic shift influenced by punk and new wave. The Gazette reports that more than $100,000 is devoted to adding a punk décor, overseen by Gilles Gagné, described as “Canada’s answer to Salvador Dalí.” This hybridization of punk and disco reflects the club’s effort to adapt to the decade’s evolving cultural trends. 26

6. Radio, promotion, and “event”: the club in the media

Beyond architecture and technology, disco is powered by another engine: promotion. By the late 1970s, clubs work to maintain the status of a “place to be” through mentions, nightlife columns, society pages, and sometimes explicit media collaborations.

A February 1979 notice points to a live show (a radio broadcast) from the discotheque, illustrating a strategy that turns the night into a media event: the dancefloor becomes both a broadcast set and a place to dance. 8

The nightclub as a “studio”

Live broadcasts from inside a club follow a typically disco logic: make the city’s energy visible, suggest the venue is “beating” in rhythm with Montreal, and extend the party beyond the walls.

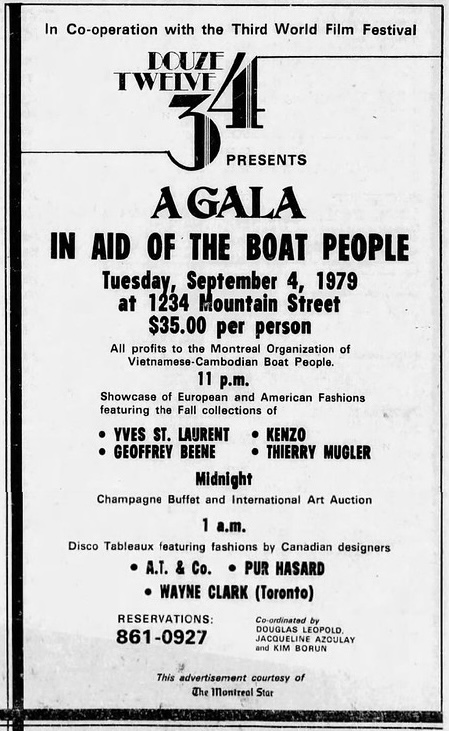

In 1979, the Club 12-34 also serves as an “event” showcase for charitable and society activities. A press notice announces a benefit gala for the Montreal Organization of Vietnamese-Cambodian Boat People, organized in collaboration with the Third World Film Festival, combining fashion shows (including collections associated with Yves Saint Laurent, Kenzo, Thierry Mugler, and Geoffrey Beene), a buffet, an auction, and a disco segment. 20

Toward a “Studio 54” image (1979)

In early 1979, Disco 1234 is successful enough to consider moving further upmarket. Management announces the upcoming opening of a private lounge called “Inner Sanctum”, reserved for members and accessible only with a card costing $300 per person.

The initiative clearly targets Montreal’s jet set, while maintaining a separate VIP card system that simply allows holders to bypass the line at the door.

The club also claims it wants to adopt an image inspired by New York’s legendary Studio 54, with the introduction of animated effects, a bubble machine, and a special entrance for privileged guests.

“Disco 12-34 is actively trying to adopt the image of Studio 54.” 38

By late 1980, the Club 12-34 expands its entertainment offer with spectacle attractions, including a mechanical bull. The Gazette publishes a photo showing Mike Bookalam riding it inside the club, illustrating the integration of “Urban Cowboy”–style elements into the disco experience. 25

7. Entry, selection, and doormen: the club’s “frontier”

In the disco era, entering a nightclub was not a simple transition: it was a social frontier. Doormen filtered access based on dress, attitude, and perceived “vibe.” A 1981 article on club bouncers describes how admission itself became a performance: lines, unspoken negotiations, dress codes, and discretionary power. 9

Contemporary accounts also report practices of exclusion and discrimination. These elements are important to document not to normalize them, but to understand how access politics were part of nightlife culture. 9

The entrance as theatre

In disco mythology, “getting in” often meant entering a parallel world: light, music, crowd, prestige. The selective door reinforced this sense of threshold and helped manufacture exclusivity.

ID checks and liquor permit enforcement

In 1986, a reader of The Gazette reported being denied entry to L’Esprit despite presenting multiple forms of ID. Management justified strict identification policies as necessary to protect their liquor license and prevent underage drinking. 34

8. Publicity, columnists, and conflicts of interest

Downtown Montreal nightlife in the late 1970s was sustained by a dense ecosystem of advertising, entertainment pages, “gossip” columns, and promotional partnerships. An August 1979 article in The Gazette discusses how certain nightlife columnists also worked as publicists for the very venues they covered. The text names the 1234 among the clubs involved—an essential clue for understanding how a venue’s reputation could be manufactured in print, not only earned on the dancefloor. 10

In a museum-style reading, this matters because the history of a club is not just music and architecture; it is also narrative: who talks about the place, how they frame it, and what interests shape that framing.

Michael Bookalam: from Montreal nightlife to criminal networks

Behind the club’s glamorous public image, the press record also points to a more troubled dimension connected to one of its former owners, Michael Bookalam. In Canadian and U.S. reporting from the early 1980s, Bookalam appears at the intersection of nightlife entrepreneurship, business interests, and cross-border organized crime. 46

Court coverage and judicial briefs associate him with drug-trafficking networks (including amphetamines and heroin) operating between the New Jersey, Quebec, and Montreal corridors. 43, 44, 45

A figure of Montreal nightlife

In Montreal, Bookalam is identified as a former co-owner of the 1234, a venue whose early years explicitly pursued an upscale, Studio-54-like aura—private rooms, VIP access, and a carefully cultivated “jet set” image. 38

Michael Bookalam: a promoter from Montreal’s elite circles

Born in 1952 into a wealthy Lebanese-Canadian family, Michael Bookalam grew up in a privileged environment. Press mentions connect his father to the Montreal company Kiddie Togs, and note a family link to future TV personality and businessman Kevin O’Leary.

As a student at Bishop’s, he was profiled as an athlete (football and hockey), receiving substantial visibility in regional newspapers in the late 1960s and early 1970s. That image of a charismatic young entrepreneur helped legitimize his role when the Club 12-34 launched in 1978. 36

Beyond nightlife, reporting also links Bookalam to the Montreal garment industry, with business connections on Port-Royal, an area long associated with the city’s textile sector. 46

Links to international trafficking networks

Coverage identifies him in cases involving cross-border trafficking and names other figures in the same orbit, including Bob Anka, a Montrealer connected in court testimony to smuggling operations between Quebec and the United States. 43

Testimony cited in press accounts describes transactions and routes involving Montreal, Philipsburg, Burlington, and Newark, with Bookalam portrayed as a key intermediary. 43, 44

The Barber case “shadow”

Bookalam’s name also appears in the broader context of the investigation into the 1983 killing of Albert “Al” Howard Barber, a U.S. drug trafficker whose body was found buried near Sainte-Adèle. 39, 40, 42

While not presented as the killer, Bookalam is reported as moving within the same criminal universe as Frank Christopher Crump, a major American organized-crime figure discussed in the case. 39, 40, 41

A more nuanced portrait: the man behind the headlines

In a 1987 interview in The Gazette, Bookalam attempts to distance himself from his criminal past, speaking of mistakes, ambition, and the desire to rebuild after years marked by prison and scandal. 46

“Maybe I keep those memories to remind me never to go back.”

As a historical case, Bookalam’s trajectory illustrates a well-documented reality in 1970s–1980s Montreal: a grey zone where nightlife, legitimate business, and criminal networks sometimes overlapped. In that light, the 1234 story includes not only glamour and spectacle, but also surveillance, controversy, and the risks of the era’s nightlife economy.

9. Disco decline, renovations, and repositioning (1980–1981)

By the early 1980s, disco was losing momentum in Montreal, and the Club 12-34 was no exception. In May 1981, The Gazette ran a revealing piece titled “Music turns sour for Disco 1234,” describing a temporary closure amid financial rumours, liquor-licence concerns, and major renovation work. 27

Owner Sol Zuckerman framed the shutdown as deliberate: the club was being reworked from the inside out. The iconic light columns were removed, two bars were closed, a new mezzanine was added, and decorative greenery was introduced to shift the atmosphere. The strategy was explicit: to relaunch as a chic cocktail bar aimed at a 25–40 clientele, rather than a mass disco venue. 27

The end of the disco era

The 1981 discourse signals a major cultural shift. Disco—once synonymous with novelty and profitability— is now treated as a fading trend. The 12-34’s pivot shows how venues tried to survive by changing identity: less “temple of dance,” more “upscale bar.”

The article also acknowledges financial strain. Zuckerman conceded that some rumours were grounded in reality, including bounced cheques and the absence of a bank credit line. 27

The revamped venue was slated to reopen on June 9, 1981, with a more intimate, polished feel. 27

By December 1981, The Gazette described Twelve 34 as a club oriented toward rock’n’roll and Motown, offering free admission and a looser vibe. The building’s funeral-chapel past is still referenced, but the original disco identity has clearly faded. 28

From disco megaclub to chic music bar

In under four years, the 12-34 shifts from a spectacle-driven disco megaclub to a renovated music bar, illustrating how fragile nightlife models can be when they depend on fast-moving cultural trends.

Paradoxically, the “1234” brand retained commercial value even as disco declined. A May 1981 advertisement for a “Super Disco Train to New York” still promoted the venue as “Canada’s #1 Disco,” leveraging name recognition to sell an internationalized disco fantasy. 29

The 12-34 thus becomes an emblem of the post-disco transition: a venue reshaping its identity while continuing to capitalize on the memory of an era.

10. After disco: transformations, new names, and documentary “traces” (1980s–1990s)

Like many disco-era megaclubs, the 12-34 belonged to a specific moment. By the early 1980s, both the aesthetics and the business model of disco were changing. Yet the building at 1234 Mountain Street continued to function as a nightlife address—ready to host new concepts and new identities.

10.1 1982: society nightlife and stage acts — “Disco 1234” / Twelve 34

In August 1982, a society brief places Paul Anka partying until 2 a.m. at Disco 1234 on Mountain Street and mentions a link to owner Mike Bookalam. 30

1982: Village People at Club 1234 — Disco as a Media Event

Despite the gradual decline of disco in the early 1980s, Club 1234 continued to host major events. A report published in Télé-Radiomonde on September 19, 1982 reveals that members of Village People, including Glenn Hughes, traveled by motorcycle from New York to Montreal in order to launch their album Fox on the Box at Club 1234.

The album launch attracted more than 600 people and was broadcast live on the radio show “5 à 10 live” on CKMF, hosted by Guy Aubry. The event also featured several disco and new wave artists, including The Flirts, Thierry Pastor, Freddie James, Chantal (Vogue duo), and Chris Mills.

This media coverage confirms that, even after disco’s peak, 1234 remained a site of international promotion, an event-based radio studio, and a media visibility platform for pop culture. The club thus maintained its role as a cultural showcase well beyond the strict disco era.

The presence of journalists, radio representatives, and music-industry figures highlights the continued importance of 1234 as a broadcast platform linking music, media, and nightlife in the early 1980s. 51

In November 1982, an advertisement for a stage act titled “Knights of Illusion” (mime / magic) lists Club Twelve 34 at 1234 Mountain St., confirming that entertainment programming persisted beyond the original megadisco format. 30

10.2 1984: Twelve 34 reconfigured — “Lips” (piano lounge) and “Shooter’s”

In 1984, mentions in The Gazette describe an internal reconfiguration: a piano lounge called “Lips” and a second bar identified as “Shooter’s”. The reporting also notes a semi-private section where clients could keep bottles labeled with their names—evidence of a more segmented, upscale bar experience. 30

10.3 1986: L’Esprit — glamour, media strategy, and nightlife revival

In August 1986, the address regained major visibility with the reopening of the club as L’Esprit, staged as a large-scale public-relations event. 32

Opening-night coverage highlights Grace Jones (dressed by Issey Miyake) and singer Eartha Kitt, emphasizing glamour and the desire to reposition the site as a prestigious nightlife destination. 32

Anglophone press notes that L’Esprit occupied the former Disco 1234 site and underwent extensive renovations. The project is linked to brothers Maurice and Marc Gatien, who aimed to create a club inspired by the nightlife scene in Atlanta. 33

L’Esprit: heir to the 12-34

The press explicitly situates L’Esprit on the former Disco 12-34 site, confirming continuity of nightlife use at the address despite changing names and concepts.

In March 1992, a brief report places an incident “inside L’Esprit discotheque” at 1234 Mountain St., showing that the address remained coded as nightlife well after the disco peak. 11

The power of an address

Even when names change, an address can retain a nightlife identity. Police briefs, listings, ads, and guides become documentary “traces” that map continuity: the space remains socially understood as a place to go out, even as music styles and audiences evolve.

11. Legacy: 12-34 as a Symbol of Montreal’s Disco Era

Club 12-34 remains a landmark in the collective memory of downtown nightlife. Its trajectory — spectacular opening in 1978, the peak of the mega-disco era, post-disco transformations, the persistence of the address, and its 2004 relaunch — condenses several core themes of Montreal’s nightlife history: adaptive architecture, technology as prestige, crowd-based economics, and media narratives.

From a museum perspective, the significance of 12-34 is twofold: (1) it represents a textbook case of the “discotheque-machine” (sound, light, spatial spectacle), and (2) it illustrates the power of commercial memory — how the disco past becomes a reusable cultural asset. 1, 12, 13

12. 2004: Revival, Capital, and Nostalgia — Club 12-34 “Reloaded”

In 2004, the address was revived under the name Club 12-34 through a relaunch strategy explicitly built on the site’s brand equity — the idea of reactivating a 1970s reputation and converting it into commercial value. The press reported an investment of approximately $1.5 million to reopen the club in a building with a storied past. 12, 13, 14

The partners behind the project were named: Tony Loddo, Johnny Setaro, MC Mario Tremblay, and Marco Iannone (Montage Management). The strategy included leveraging a DJ/media personality to reinforce the club’s sonic identity and public visibility. 12, 15

“It’s time to boogie again”

The 2004 relaunch relied on the language of memory: the venue was presented as a “fabled space,” and its disco-era reputation (stars, legends, dancefloor mythology) was used to promise a return to experience — a way of selling the past as a present-day attraction. 16

2005–2011: Violence, Gangs, and Loss of Control

By the mid-2000s, Club 1234, then owned by Giovanni Setaro, Jean Faille, and former Montreal Canadiens DJ Mario Tremblay, remained a popular nightlife destination, particularly due to the popularity of DJ MC Mario.

However, according to a report by the SPVM (Montreal police), the venue gradually became a public safety concern. Between 2005 and 2010, more than 40 violent incidents were recorded: mass brawls involving up to 50 people, stabbings, assaults on security staff, gunfire, arrests of armed individuals, and patrons falling from the second floor.

Police officers responding to incidents reported being surrounded, assaulted, bitten, and targeted with projectiles. The recurring presence of street gangs was also documented, as well as the involvement of a former manager with organized crime.

The issue of minors was of particular concern. In 2006, officers discovered between 100 and 150 teenagers aged 16–17 inside the club. In 2009, a minor was reportedly violently assaulted by a bouncer.

A scheme was allegedly put in place to allow underage patrons to enter illegally by paying a surcharge to a promoter, according to a report submitted to the Régie des alcools, des courses et des jeux.

In 2011, the Régie formally summoned the club’s owners, at the request of police, to evaluate the loss of control of the establishment. 47

From Nightclub to “Supper Club”: Yoko Luna, Geisha and the Haunted Imaginary of 1234 (2013–2022)

In the spring of 2013, Club 1234, located at 1234, rue de la Montagne, officially closed its doors, marking the end of a cycle for this well-known downtown nightclub. Following the closure, DJ and co-owner MC Mario announced a new project called “5”, a name that refers both to the logical continuation of “1234” and to the structure of the concept itself, organized around five components: a restaurant, a lounge, a bistro, a bar, and a terrace. The opening was then announced for early summer 2013. 55

After several reconfigurations, the address entered a new phase of transformation in the early 2020s. In October 2021, it was announced that Club Le CINQ, the most recent incarnation of the site, would be converted into a Japanese restaurant and supper club under the name Geisha. The project was developed by the Jegantic Hospitality Group, founded by John E. Gumbley, and reflected a deliberate repositioning of the venue toward a gastronomic and experiential model. 56

The project materialized in 2022 with the opening of Yoko Luna, a high-end Japanese establishment of the supper club type, occupying approximately 20,000 sq ft. Official communications emphasized an “dreamlike” and immersive décor, including a whisky lounge, a cocktail bar, a large dining room, and outdoor terraces, extending the site’s long-standing role as a venue for nightlife entertainment, now framed within a contemporary gastronomic context. 57

Alongside this promotional discourse, the earlier history of the building— originally a funeral home in the early twentieth century, later followed by several nightlife venues—has fueled a media imaginary associated with so-called “haunted” locations. An investigation published by Haunted Montreal relays employee testimonies describing unexplained phenomena (cold drafts, old music, whistling sounds, incense-like odors) and claims that exorcism rituals were performed prior to the restaurant’s official opening. 57

The same article further asserts that the former morgue was located in the basement, in the area now occupied by the restrooms, and reports experiences described as attempts at communication with spirits. These elements, unverifiable from a historical standpoint, belong more to the narrative and folkloric register than to strict heritage documentation. 57

From a historical perspective, these accounts primarily contribute to the construction of a symbolic memory of the site. They illustrate how the building’s funerary and later nocturnal past continues to shape its public image, even after its transformation into a contemporary gastronomic establishment. The address at 1234, rue de la Montagne thus remains marked by a superimposition of layers—funeral home, nightclub, supper club—sustaining its persistence within Montreal’s collective imagination.

Notes & Sources

- The Gazette, December 2, 1978 — “High chic and high profits energize Montreal’s discos”, Julia Maskoulis. Analysis of the profitability and aesthetic of Montreal nightclubs during the disco era.

- Municipal archives and commercial directories — Former Wray-Walton-Wray Funeral Chapel, 1234 Mountain Street.

- Advertisements and promotional notices (summer 1978) — Mentions of the opening and marketing of Club 1234 (address, concept, imagery, invitations).

- Press articles and promotional materials (1978–1979) mentioning an investment of approximately $1 million to convert Club 1234 and a capacity of about 1,500 people.

- Cultural columns and nightlife coverage (summer–fall 1978) describing the atmosphere of early disco nights in Montreal, the staging of clubs, and the importance of novelty.

- The Gazette (Montreal), August 5, 1978, p. 23 — Preview article announcing the opening of a new nightclub at 1234 Mountain Street, mentioning the former funeral chapel (Wray-Walton-Wray) and its transformation by “speakers and lights.” Key source for the opening date (August 8, 1978) and the building conversion narrative.

- The Montreal Star, September 28, 1977, p. 51 — Real estate listing describing 1234 Mountain St. as a “prime downtown location,” available around December 1, 1977. Useful for documenting the pre-discotheque transition phase.

- The Gazette, February 17, 1979, p. 75 — Announcement of a live FM-96 radio broadcast from a downtown discotheque associated with 1234. Indicator of the event-driven media strategy of disco-era clubs.

- The Gazette, January 10, 1981, p. 41 — “Club doormen reveal secret of getting in” (Joan Danard). Context on door policies, bouncers, and admission practices, including reported discrimination.

- The Gazette, August 15, 1979, p. 3 — “Psssst! These men are gossip kings.” Mentions promotional work done for clients including Club 1234. Key source on the role of publicity and media influence in nightclub reputations.

- The Gazette, March 9, 1992, p. 3 — Brief police report situating an altercation inside L’Esprit nightclub at 1234 Mountain St. Evidence of the address’s continued nightlife use in the early 1990s.

- The Gazette, September 20, 2004, p. 26 — “Managing” (continued from B1). Details the relaunch of Club 1234 by Montage Management (Tony Loddo, Johnny Setaro, MC Mario Tremblay, Marco Iannone). Major source for operational data and business strategy.

- The Gazette, September 20, 2004, p. 23 — “As easy as 1-2-3-4” (Peter Diekmeyer). Mentions the $1.5 million investment and the goal of relaunching the venue. Nostalgic framing of the 1234 brand.

- The Gazette, October 2, 2004, p. 63 — “A brand-new Club 1234 comes back to fabled space” (John Griffin). Describes the address, relaunch, and disco-era legacy of the site.

- The Gazette, September 20, 2004, p. 26 — “Vital statistics” box listing operational facts, contact details, and staffing figures.

- The Gazette, September 20, 2004, p. 2 — Teaser headline: “It’s time to boogie again.” Frames the relaunch through disco-era nostalgia.

- MONTRÉAL-MATIN, June 21, 1978, p. 8 (column “Les Gens”) — Announcement of a new nightclub at 1234 Mountain Street. Mentions the former funeral chapel, stained-glass décor, and plans for a large entertainment complex. Includes biographical details on Gary Chown.

- MONTRÉAL-MATIN, September 14, 1978 — Article reporting a violent incident that led to the temporary closure of Club 1234.

- The Montreal Star, February 12, 1979, p. 29 — Fashion page “The lady in red” featuring photos taken at 1234 Mountain Street. Shows the club as a media and fashion showcase.

- The Montreal Star, August 31, 1979, p. 11 — “Douze / Twelve / 3-4 presents a gala in aid of the Boat People.” Charity event at 1234 Mountain Street featuring fashion shows, champagne buffet, and disco tableaux.

- The Gazette, October 13, 1979, p. 58 — Social column mentioning a party linked to 1234 Mountain St.

- The Gazette, March 27, 1979, p. 56 — Column mentioning laser light demonstrations associated with 1234 Mountain St.

- The Montreal Star, May 14, 1979, p. 26 — “Toys and discos” (Brian Dunn). Profile of Sol Zuckerman referencing Club 1234.

- The Gazette, March 25, 1980, p. 53 — Reports that Disco 1234 charged a $9 Saturday cover to finance a four-color laser system.

- The Gazette, December 20, 1980, p. 29 — Photo showing Mike Bookalam riding a mechanical bull inside Disco 1234.

- The Gazette, January 16, 1980, p. 57 — “Punk, it seems is marrying disco” (Thomas Schnurmacher). Mentions a $100,000+ punk décor renovation at Disco 1234 by Gilles Gagné.

- The Gazette, May 12, 1981, p. 3 — “Music turns sour for Disco 1234.” Details financial trouble, liquor permit issues, renovations, and repositioning toward a “chic bar.”

- The Gazette, December 19, 1981, p. 82 — Brief announcing Twelve 34’s shift to rock’n’roll and Motown with free admission.

- The Gazette, May 2, 1981, p. 70 — Advertisement for the “Super Disco Train to New York” promoting Club 1234 as “Canada’s #1 Disco.”

- The Gazette, August 20, 1982, p. 21 — Mentions Paul Anka partying at Disco 1234 with Mike Bookalam. The Gazette, November 27, 1982, p. 38 — “Knights of Illusion” ad at Club Twelve 34. The Gazette, June 21 & July 13, 1984 — Mentions “Lips” piano bar and “Shooter’s” bar inside Twelve 34.

- La Presse, August 23, 1985 — Heritage notice stating the building was constructed in 1859 for David Wood, occupied by Sir Alexander Galt in 1865, and converted into a funeral home in 1902.

- La Presse, August 8, 1986 — Article on the reopening of L’Esprit featuring Grace Jones and Eartha Kitt.

- The Gazette, May 1, 1986, p. 45 — Reports renovations at the former Disco 1234 site for the launch of L’Esprit.

- The Gazette, October 15, 1986, p. 52 — Letter describing strict ID policies at L’Esprit to protect liquor permits.

- Haunted Montreal, May 2022 — “Update on the Haunted Nightclub at 1234 de la Montagne.” Reports paranormal claims and exorcisms during the Yoko Luna restaurant conversion.

- The Montreal Star, June 11, 1977, p. 140 — “Bogie boogieing.” Profile of Bogart’s nightclub and Michael Bookalam’s early career.

- La Presse, June 27, 1978 — Obituary of Sharon Bookalam, sister of Michael Bookalam.

- The Gazette, February 13, 1979, p. 44 — “Private place.” Announces the Inner Sanctum VIP room and Studio 54-inspired image.

- La Tribune, May 10, 1991 — Article on the reopening of the Albert Howard Barber murder case.

- La Presse, May 10, 1991 — Investigation into the Barber murder naming Frank Crump, Michael Bookalam, and John Coley.

- La Presse, August 16, 1991 — Reports on Quebec authorities seeking Frank Crump’s extradition.

- The Gazette, August 5, 1983 — “Man’s body identified as U.S. fugitive.”

- The Record, July 4, 1984 — “Judge to rule if Anka guilty in Canada.”

- The Record, July 24, 1984 — “Man cleared on international ‘speed’ rap.”

- The Record, March 21, 1985 — Brief judicial update involving Michael Bookalam.

- The Gazette, March 19, 1987 — “Ex-drug dealer shirks the issue.” Profile of Michael Bookalam during his rehabilitation phase.

- La Presse, September 14, 2011 — Vincent Larouche, “Un bar de la rue de la Montagne sous la loupe.” Reports over 40 violent incidents at Club 1234 between 2005 and 2010, gang activity, underage entry schemes, and the RACJ investigation.

- Wm. Notman & Son Ltd., 1932 — “Joseph C. Wray funeral parlour, Mountain St., Montreal.” Gelatin silver film negative (silver salts on film), 19.9 × 25 cm. Photography Studio archive, Notman Photographic Archives, McCord Museum (Object No. VIEW-25239). Photograph showing the Joseph C. Wray funeral parlour on de la Montagne Street in the early 1930s, documenting the building’s use as a funeral home decades before its transformation into a discotheque. Credit: Purchase with funds donated by Maclean’s magazine, the Maxwell Cummings Family Foundation and Empire-Universal Films Ltd. McCord Museum Collection — Not on view.

-

Armand Trottier, April 8, 1979 —

Photographic file:

“Federal Liberal Convention in the riding of Saint-Jean” /

“‘1234’ Discotheque, de la Montagne Street”.

The file contains a series of photographs documenting two separate reports:

a Federal Liberal Party convention in the riding of Saint-Jean, and a photo report

on the 1234 Discotheque, located on de la Montagne Street in Montreal.

The images notably show Paul-André Massé and Jacques Rancourt

in the context of the Club 1234 reportage.

Archival reference: P833, S5, D1979-0142

Collection: La Presse Fonds

Repository: National Archives in Montreal (BAnQ) The file includes 17 photographic items. - The Gazette, July 9, 1979 — “Ted Blackman: He made Montreal into a disco city.” Article describing Montreal’s nightlife boom, disco culture, crowd dynamics, and international reputation during the late 1970s.

- Télé-Radiomonde, September 19, 1982. Feature on the promotional event held at Club 1234 for the album Fox on the Box by Village People. The report documents the motorcycle trip made by members of the group from New York to Montreal, the presence of Glenn Hughes, the live radio broadcast on CKMF’s “5 à 10 live” show hosted by Guy Aubry, and the participation of several disco and new wave artists including The Flirts, Thierry Pastor, Freddie James, Chantal (Vogue duo), and Chris Mills. The event reportedly attracted over 600 attendees.

- The Gazette, Montreal, July 9, 1979 — Ted Blackman, “He made Montreal into a disco city”. Column describing celebrity attendance at Club 1234, including Guy Lafleur (noted for his “chic” style with a crocodile-skin bag), Omar Sharif, as well as models, producers, and social elites. The article presents 1234 as a prestigious social stage where sports, cinema, fashion, and nightlife intersect.

- The Gazette, August 15, 1979, p. 3 — Ted Blackman, “Psssst! These men are gossip kings”. Article on Montreal’s nightlife columnists and social commentators (Tommy Schnurmacher, Michel Girouard, Douglas Leopold, John Burgess). The text highlights conflicts of interest between journalism, public relations, and event promotion, noting that some writers also worked as hosts or publicists for venues such as Club 1234.

-

Photo credit — Hugo Trottier, photograph taken at Club 1234 (Montreal).

Reference: archival image associated with the venue, useful for documenting the atmosphere, décor and/or clientele of 1234. -

MONTREAL.TV, May 25, 2013 —

“Fermeture du Club 1234 : bienvenue au 5”.

Reference: announcement of the closure of Club 1234 at 1234, rue de la Montagne; mentions MC Mario as DJ and co-owner; presents the new project “5”, structured around five components (restaurant, lounge, bistro, bar, terrace); opening announced for early summer 2013. -

MTL BLOG, October 15, 2021 — Ilana Belfer,

“Club Le CINQ Will Become A Japanese Steakhouse & Supper Club”.

Reference: announcement of the conversion of Club Le CINQ, the most recent incarnation of the former Club 1234, into a Japanese restaurant and supper club named Geisha; project led by the Jegantic Hospitality Group (founder: John E. Gumbley); opening described as “coming soon,” with the venue explicitly identified as 1234, rue de la Montagne. -

HAUNTED MONTREAL, 2022 —

article devoted to Yoko Luna and the earlier history of the

building at 1234, rue de la Montagne.

Reference: discusses the site’s funerary past (former funeral home), the succession of nightlife venues, and a media narrative associated with so-called “haunted” locations; relays employee testimonies describing unexplained phenomena (cold drafts, old music, whistling sounds, incense-like odors) and claims that exorcism rituals were performed prior to the opening of Yoko Luna. These elements belong to a narrative and folkloric register and do not constitute historically verifiable facts.