Théâtre National (Montréal)

Also known as the Théâtre National Français, and later Le National, this theatre inaugurated in 1900 on Sainte-Catherine Street East has been a pillar of French-language theatre, vaudeville, and burlesque in Montreal — from Julien Daoust and Paul Cazeneuve to La Poune (Rose Ouellette), and on to the stage revival of the 1990s and Belle et Bum.

1. Overview

Designed by Albert Sincennes and Elzéar Courval for an emerging Francophone company, the Théâtre National Français opened on August 12, 1900 at 1440 Sainte-Catherine Street East (today 1220). Built by impresario Julien Daoust, it was taken over a few weeks later by Georges Gauvreau, who officially reopened it on September 4, 1900. [1]

2. Origins (1900) & early years

In the wake of the Monument-National (1893), Le National became a creation stage for original French-Canadian works. An electric bell system connected the auditorium to the neighboring Des Deux Frères restaurant, calling patrons back at the end of intermissions. [1], [6], [8], [10]

Faust, launch costs, and a rapid transfer

The expenses tied to construction and to mounting the first production, Faust, left Julien Daoust without the resources needed to sustain operations. After only two weeks of activity, he transferred the enterprise to Georges Gauvreau, a businessman and restaurateur, who stabilized the theatre’s management and finances. [10]

3. First golden age: Gauvreau & Cazeneuve (1901–1910s)

Paul Cazeneuve: a “total” artistic director

As early as March 1901, Gauvreau brought in Paul Cazeneuve, an American of French origin, as artistic director. The scope of his role was enormous: set the weekly programming, design staging and scenic effects, hire performers, cast roles — while also frequently keeping leading parts for himself. [10]

A mission upheld: a stage for French-Canadian artists

Gauvreau and Cazeneuve maintained the essence of Daoust’s project: to provide a stage for French-Canadian artists, both performers and playwrights. Cazeneuve put local actors under contract and quickly made room for the creation of new dramatic texts by local authors. The Théâtre National thus became a cornerstone in the rise of Quebec theatre. [10]

4. Julien Daoust: a pioneer of Quebec theatre

Condensed biography

Julien Daoust was born in 1866 in Saint-Polycarpe (Montérégie). He began in theatre as a teenager alongside Blanche de la Sablonnière (the “Canadian Sarah Bernhardt”), then left Quebec in 1890 for a career in New York, performing in French and English for roughly eight years. Back in Montreal, noting how little space French-Canadian artists held on professional stages (with leading roles often awarded to performers from France), he built the Théâtre National to showcase local talent. [10]

A complete theatre-maker (actor, playwright, director)

Daoust was an acclaimed actor, as well as a prolific writer and an audacious director. He worked across genres (melodrama, one-act comedy, patriotic drama, current-affairs revue), with religious dramas among his biggest successes. He innovated in dramaturgy, scenography, and staging, and organized tours for Francophone communities in the United States. [10]

Noted innovations (1898, 1907…)

Milestones often cited include a North American staging of Cyrano de Bergerac (Rostand) in 1898, early-20th-century experiments with projected scenery, and the early use of popular speech (now associated with “joual”) decades before its breakthrough on stage. Even if his name is sometimes eclipsed in popular narratives, his role in “clearing the path” is essential to understanding Quebec theatre’s evolution. [10]

5. Audience, troupe, and pace: “pensions” & discipline

A working-class neighborhood, affordable tickets

The Théâtre National stood in the heart of a French-speaking working-class district (workers and families). To secure attendance, Gauvreau and Cazeneuve maintained an affordable ticket policy: entertainment, but also a form of artistic education for people with limited access to luxury. At times, however, the audience also included prominent figures (senators, consuls, mayors and former mayors, professors, and other notables) spotted in the boxes on opening nights or for highly anticipated shows. [10]

The “pensions” system: a stable troupe

To sustain a new show every week, management adopted the pensions system: contracting a little more than a dozen performers for an entire season, forming a stable and balanced troupe. Artists were hired by “emploi” (what we would call casting today) — first comic lead, ingénue, villain, first dramatic lead, supporting roles, etc. — which simplified casting, while also limiting character work due to the tight schedule. [10]

A pace unthinkable today

Performances ran daily (often twice a day) while the troupe simultaneously learned and rehearsed the next show. A testimony relayed by Joseph-Philéas Filion (via Jean Béraud) describes a strict weekly routine: morning rehearsals, night rehearsals, a Sunday general rehearsal, and time set aside for costumes and scenery — with the new show “always” opening on Monday night. [10]

6. Louis Guyon: patriotic dramaturgy (1902–1903)

Louis Guyon (1853–1933), born into a Franco-American working-class family, moved to Montreal as a child and pursued technical training (as a machinist). Active in union movements, he also stood out as a factory inspector. In parallel, he wrote for Montreal’s amateur theatre circles, before turning to patriotic plays inspired by French-Canadian identity. [10]

Denis le Patriote (1902)

In the spirit of Daoust’s nationalist mission, carried forward by Gauvreau and Cazeneuve, the National staged Denis le Patriote in the fall of 1902. Two days before opening, La Presse ran a lengthy article introducing the author and his work. Reviews following the premiere (September 15) suggest a favorable reception — while also mentioning, as was common at the time, variety attractions (for instance a troupe of New York acrobats) likely presented during intermission. [10]

Jos Montferrand (1903) and publication (1923)

The following year, Guyon presented a play centered on Jos Montferrand, already elevated to national-legend status. Ads and reviews convey palpable enthusiasm. A sign of its reach: the play was published in 1923, with information and photographs tied to its creation. [10]

7. Paul Gury (Loïc Le Gouriadec): moral theatre & major hits (1918–1923)

“Hygienist” and moral theatre after the war

Paul Gury (pen name of Loïc Le Gouriadec) became artistic director of the Théâtre National in 1918. In the post–First World War context, he wrote a trio of moralizing plays meant to raise awareness about “new” social ills seen as threatening public health and social peace: Les dopés (1919, drugs), Les esclaves blanches (1921, prostitution), and above all Le mortel baiser (syphilis), which became his greatest success. [10]

Le mortel baiser: a stage phenomenon (1920–1923)

First presented during Holy Week in 1920, Le mortel baiser stayed on the National’s bill for three consecutive weeks, then was immediately revived at the Théâtre canadien-français for at least five more weeks. Frequently restaged across Montreal, the show even toured Europe in 1923. [10]

8. Maria Chapdelaine (1923): adaptation & archival traces

Following the success of Louis Hémon’s novel, Paul Gury (Loïc Le Gouriadec) wrote a stage adaptation of Maria Chapdelaine, premiered at the Théâtre National in February 1923. Contemporary press notices reflect excitement and, especially, the pleasure of seeing French-Canadian culture honored on stage. [10]

A typescript of the adaptation is held today in the Paul-Gury fonds at Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (P841, S3, D1), with a handwritten dedication dated 1940. [10]

9. Cinema at the National: moving pictures, intermissions & survival

A theatre born at cinema’s dawn

The Théâtre National opened five years after the Lumière brothers’ earliest film screenings in France. In Montreal, as early as 1897, Parc Sohmer offered outdoor projections supervised by electrician Léo-Ernest Ouimet. [10]

Gauvreau, Ouimet, and the integration of “moving pictures” (from 1901)

As owner of the neighboring Aux deux frères restaurant, Georges Gauvreau quickly saw an opportunity: after acquiring the theatre, he began adding “moving picture views” during intermissions from 1901. Ouimet — credited with designing a particularly sophisticated electrical system for the venue — once again ran the projector. He remained employed by Gauvreau until opening his own cinema in 1906: the Ouimetoscope, very near the National. [10]

Early screenings: format, lecturer, orchestra

Gauvreau claimed the National was among the first Francophone theatres to present moving pictures as early as 1901: special intermission attractions mixing short films, historical lectures, and illustrated songs. Because films were silent, screenings could be accompanied by an orchestra and by a bonimenteur (a lecturer who explained the action and read — sometimes translating — titles and intertitles). By 1903, moving pictures became more regular within the weekly offering, while still tied to intermissions. [10]

A survival hypothesis: the projector as lifeline

One can argue that moving pictures — and later full cinema programming — helped keep the hall active during periods when staging theatre was no longer profitable. In other words: in certain downturns, the National’s endurance may owe a great deal to its screen and projectors. [10]

La création du monde (1915): projected scenery

In the fall of 1915, Julien Daoust briefly returned as artistic director and created a biblical work, La création du monde. Press clippings emphasize the “electrical effects” and the unusual scenery: rather than painted backdrops, Daoust used a projection device (lantern / apparatus brought from New York) placed upstage behind a curtain, producing sets made entirely of projections. The show’s success is suggested by a run of about two consecutive weeks. [10]

Sir Wilfrid Laurier’s funeral (1919): Ouimet’s film and rapid screening

The funeral of Sir Wilfrid Laurier took place in Ottawa on February 22, 1919. Ouimet filmed the ceremony, distributed by Pathé and screened in Montreal within a very short window. The National’s management touted an exclusivity “east of Saint-Denis,” but period newspapers indicate screenings elsewhere as well (Maisonneuve, Saint-Denis, Loew’s, Regent, etc.). The National does appear to have distinguished itself with a promotional initiative (an 18 × 14 inch photogravure). [10]

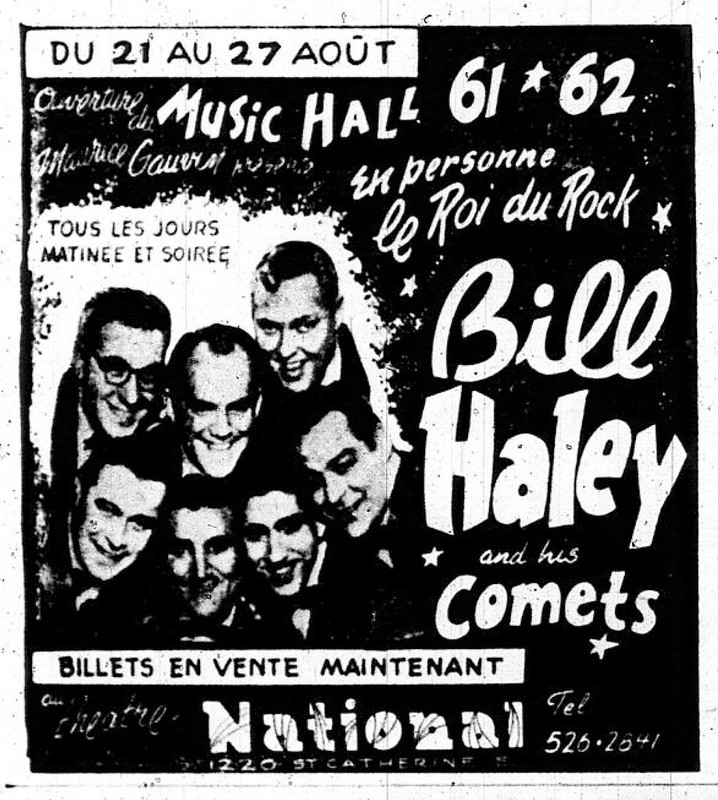

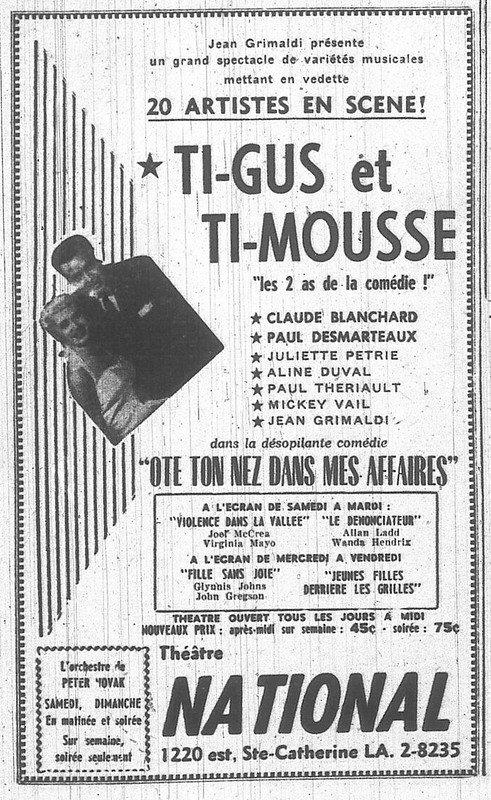

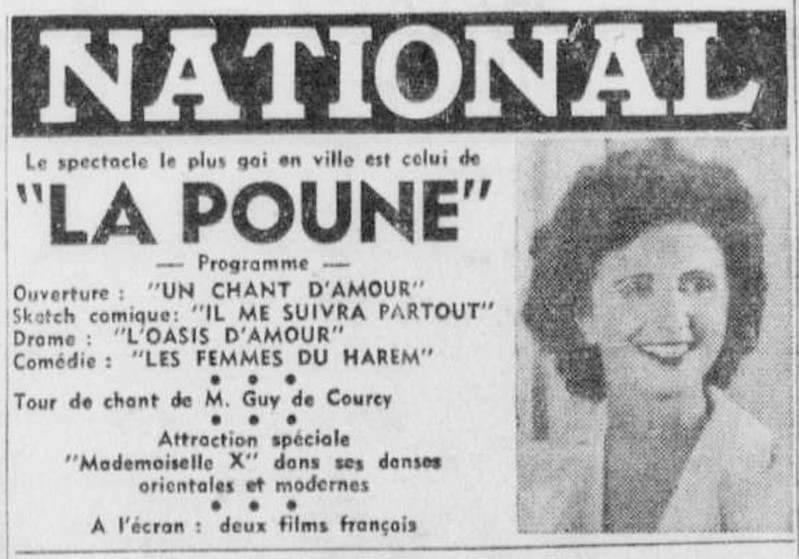

France-Film (from 1934): burlesque + French films

From 1934, under France-Film (headed by Joseph-Alexandre DeSève), programming paired burlesque and film. Before each burlesque show, two French films (still called “views”) were presented, with weekly changes reflected in contemporary advertising. [10]

From Chinese cinema to Cinéma du Village (1980s–1993)

In the early 1980s, a family of Chinese origin bought the National and converted it into a cinema dedicated to Chinese-language films. Quebec media coverage then waned and program advertising largely disappeared from Francophone papers; one trace mentions the screening of The Coldest Winter in Peking (a Taiwanese anti-communist film, banned at the time in China and Hong Kong). In 1984, the venue became the Cinéma du Village, initially envisioned as gay art-house / repertory cinema, before shifting toward gay erotic films, seen as more profitable; the enterprise lasted about ten years. [10]

10. Second golden age: burlesque & La Poune (1920s–1953)

From weekly drama to burlesque

From the 1920s on, artistic leadership became less stable and the hall shifted toward variety forms: sketches, short plays, songs, dance, and situation comedy — a blend associated with burlesque. While beloved by audiences (especially in the Faubourg à m’lasse), the genre was often dismissed by elite critics, and critical coverage dwindled. Reconstructing this history requires cross-reading paid ads, archival fonds, and specialized scholarship. [10]

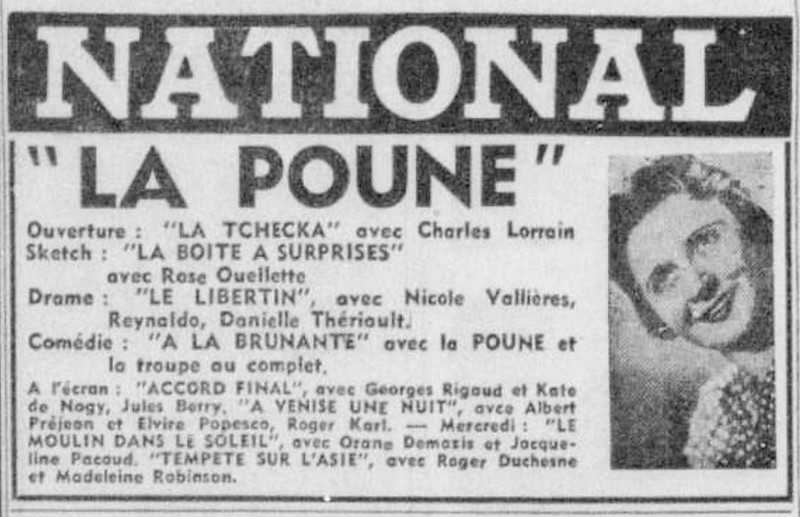

La Poune arrives (1936): a contract that became a reign

Before La Poune, the National’s burlesque scene featured, among others, Joseph and Manda Parent, Pic-Pic and Tizoune, and Olivier Guimond (Sr.). But it is Rose Ouellette, known as La Poune, who defined the venue’s legend: arriving in summer 1936 on a 10-week contract, she ultimately stayed 17 years. Sources note that at the time, her arrival made little noise in the press — “just another contracted troupe” — until history proved otherwise. [4], [10]

Show “conduct”: a stable running order, long seasons

For 17 years (often summarized as 42 weeks out of 52), La Poune and her troupe delivered evenings with a recurring structure: full-troupe opening, a one-act drama, short sketches (“bits”), attractions (songs, dance, sleight of hand, acrobatics), and a final full-length comedy. A handwritten notebook in the Gilles-Latulippe fonds (BAnQ), associated with the 1945 season, helps document these running orders; although it does not always name the Théâtre National explicitly, cross-checking (dates, performers) supports the link, and press clippings can confirm details. [10]

Galas, revues… and the xylophone

Gala nights and revues punctuated the routine: the end of the war, calendar holidays, the turn of the year. La Poune sometimes played a xylophone. According to biographical accounts (supported by images), she bought the instrument from a visiting musician, wore it out through constant use, and replaced it — with one of these xylophones now held in the collections of the Musée de la civilisation (Québec City). [10]

Alys Robi at the National: apprenticeship and loyalty

Alys Robi met La Poune in Quebec City in summer 1936, when she was only 13. Soon after, she went to Montreal and asked to join the troupe; La Poune gave her a first chance and housed her. The singer later claimed she remained about three years at the National, even if her name did not always appear in weekly ads. She continued visiting the National team on special evenings (for example, on her return from England in 1945, in her own accounts). [10]

Burlesque as musical theatre

Songs played a central role: in some testimonies, Quebec burlesque is described first and foremost as musical theatre. Archival photographs show sung numbers — sometimes at a microphone — embedded within sketches, suggesting conventions that were normal at the time (a break in the action, a featured duet, etc.). [10]

Backstage atmosphere: memory sometimes carried by literature

Certain literary depictions (not strictly historical sources) helped transmit the feel of 1940s backstage life. They are not evidence in a research sense, but when paired with photos and testimonies, they can help convey the venue’s effervescence. (For example, evocations of noisy backstage corridors crowded with people coming to greet performers.) [10]

11. After 1953: TV, cabarets & transformations

In 1953, Ouellette left a hall increasingly challenged by television and cabarets. Impresario Jean-Marie Grimaldi took over; in parallel, he bought and converted the Gayety (formerly Lili St-Cyr’s venue) into Théâtre Radio-Cité with Michael Costom, without slowing the rise of the small screen. He briefly attempted to relaunch the National (April 1958) before other operators took the lease (1960: Yvan Dufresne & Jean Bertrand). [9]

A series of metamorphoses followed: nickelodeon, vaudeville, Chinese cinema, classroom space, the ill-fated O’National (bankrupt after a month), then the Cinéma du Village, initially oriented toward gay art-house before shifting to erotic programming (1984–1993). [1], [4], [5], [6], [7], [10]

12. The Conservatoire (1968–1973): a school in the “old National”

A nomadic Conservatoire, then the National as refuge

The Conservatoire d’art dramatique de Montréal was long nomadic (Palais du commerce, above Valiquette, the upper floors of Monument-National, the basement of the Saint-Sulpice Library…). Under Guy Beaulne, national director of the conservatoires, the institution moved into the Théâtre National. Across Sainte-Catherine Street, a former factory was adapted to house administrative offices and teaching studios. [10]

A worn theatre… but a formative home

By the late 1960s, the National was described as a building that had “seen snow.” Some accounts even evoke snow occasionally falling onto the stage. Despite dust, lack of hot water, and overall condition, cohorts experienced three rigorous and decisive years of professional training, turning an imperfect place into a beloved home of learning. [10]

Summer theatre (1971): free shows and Perspectives-Jeunesse

In 1971, the cohort that entered in fall 1970 devised a plan to keep working at the Théâtre National through the summer, normally reserved for holidays. A Perspectives-jeunesse grant made it possible to mount and present two free public productions: Superdrogstore et le miroir maléfique (afternoons, for children) and Mardi la verte (evenings, for older audiences). [10]

Opening to Quebec dramaturgy: Portés disparus (1972)

At the end of 1971, François Cartier, director of the Conservatoire, asked playwright Marcel Dubé to write a piece tailored to the graduating cohort: Portés disparus. In a Quebec theatre scene undergoing revolution (1968: Cid maghané, L’Osstidcho, Les Belles-sœurs), this marked an important shift, responding to student demands to “use their own words” on stage. The text was never published; only limited traces remain — clippings, photos, a program kept by Christine Raymond, and participant memories. [10]

Last public exercise at the National: Alcide 1er (1973)

The Conservatoire ultimately left the Théâtre National at the end of the 1973 school year when the landlord refused to renew the lease for teaching spaces. The music and drama conservatoires were then unified in the Ernest-Cormier building (former courthouse; now the Quebec Court of Appeal). At the National, the last public exercise was La vie exemplaire d’Alcide 1er, le pharamineux, et de sa descendance proche, a play by Quebec author André Ricard. Contact sheets preserved in the institution’s archives offer a partial view of the show’s sequence and staging, despite their limited readability. [10]

Archives and memory: scarce traces

Accessible sources for this period remain limited: the Conservatoire had not yet systematized recording of productions. A handful of photos survive; research draws on BAnQ digital archives, selected fonds, internal Conservatoire archives, and former students’ recollections. [10]

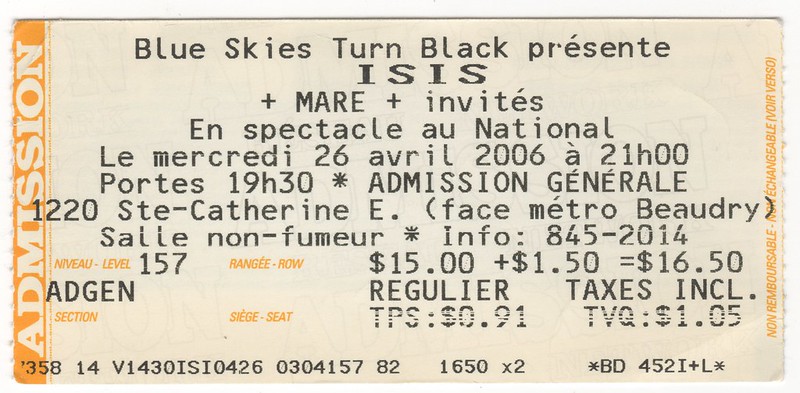

13. Revival (1995), centennial (2000) & relaunch (2006)

On March 25, 1995, the theatre reopened “in grand style”: Alys Robi inaugurated the new life of a restored National, renovated by Michel Astraudo and Gilles Laplante, with an aesthetic respectful of the venue’s spirit. [1], [2]

The 2000 centennial was celebrated more modestly than hoped due to the lack of a dedicated subsidy, but it was still marked by a gathering of “old hands.” [3]

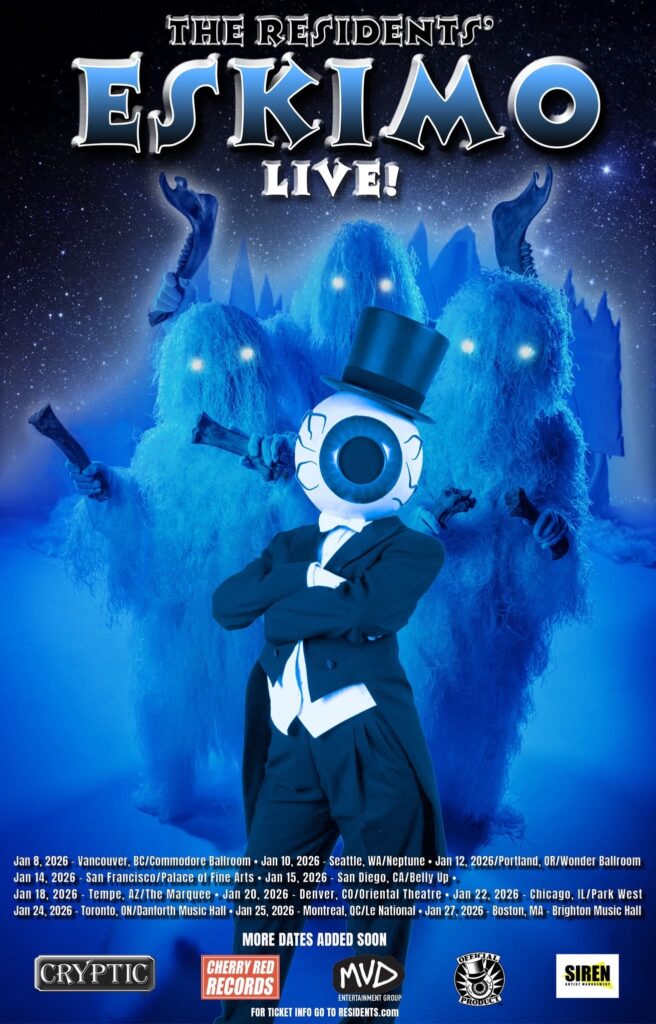

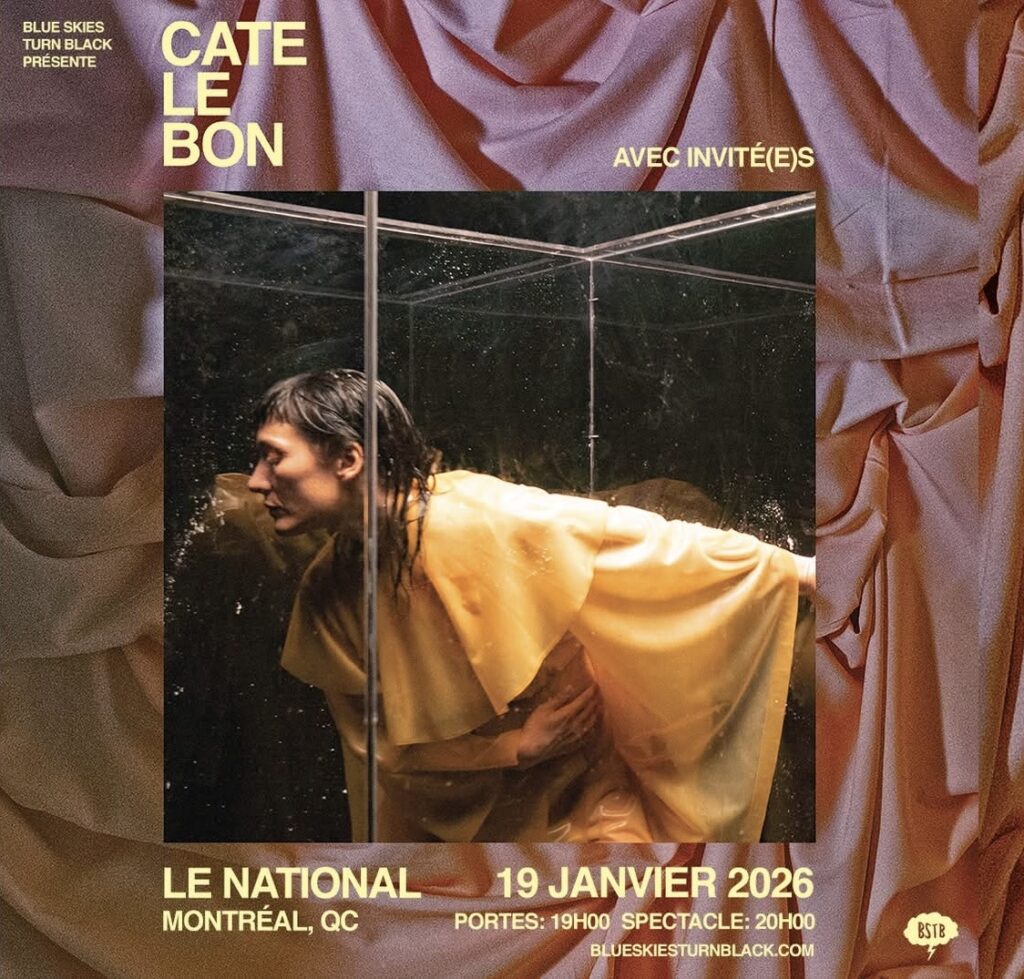

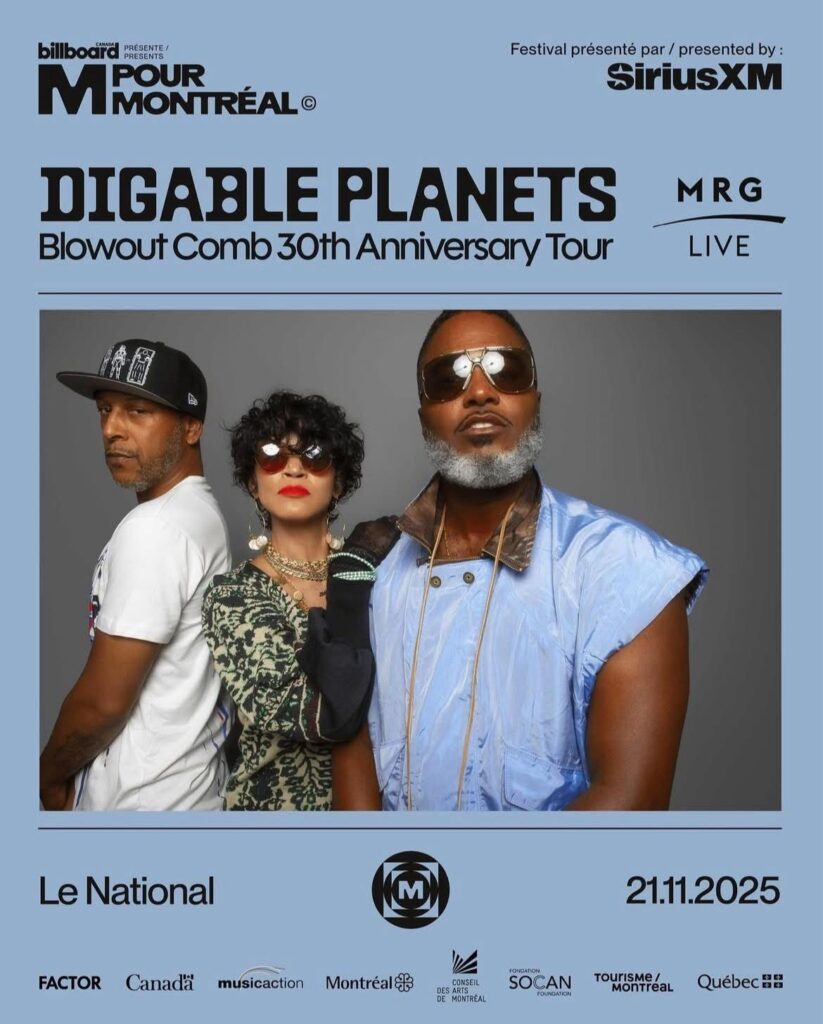

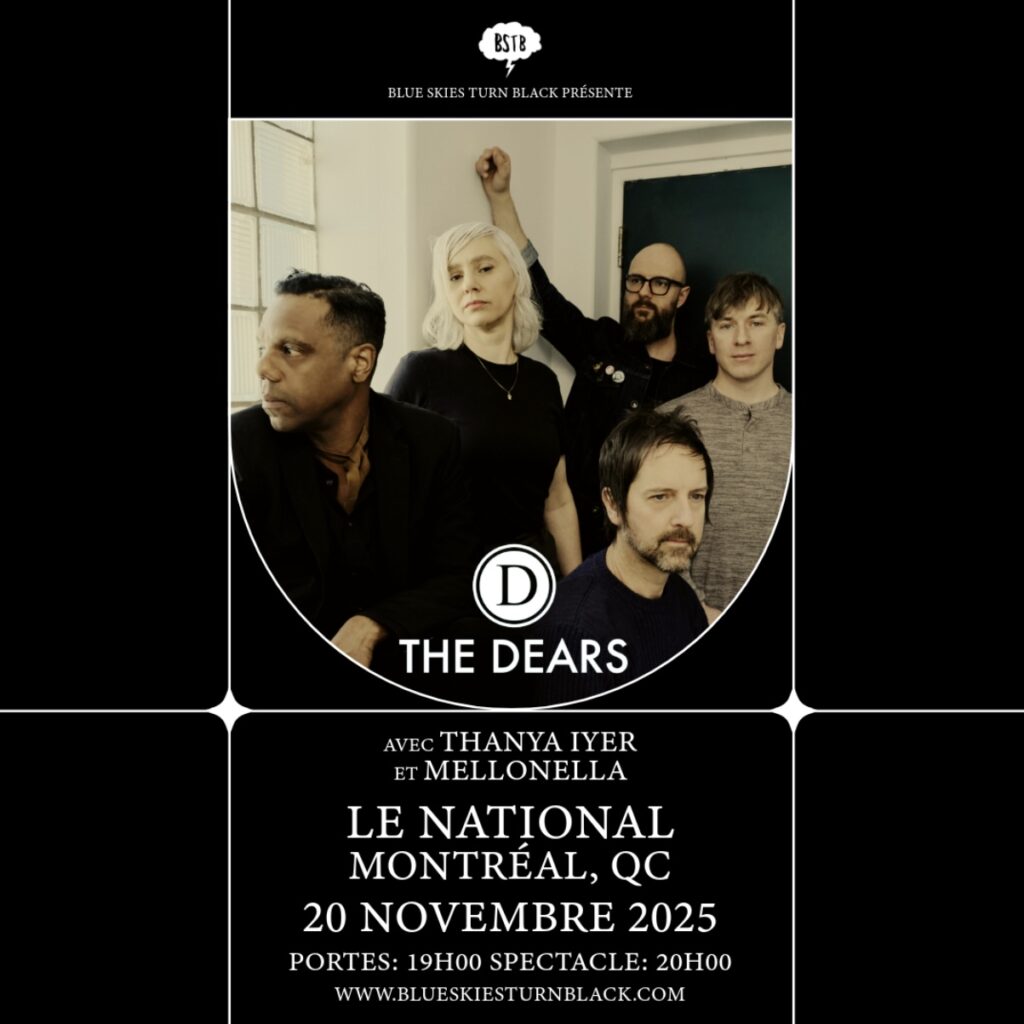

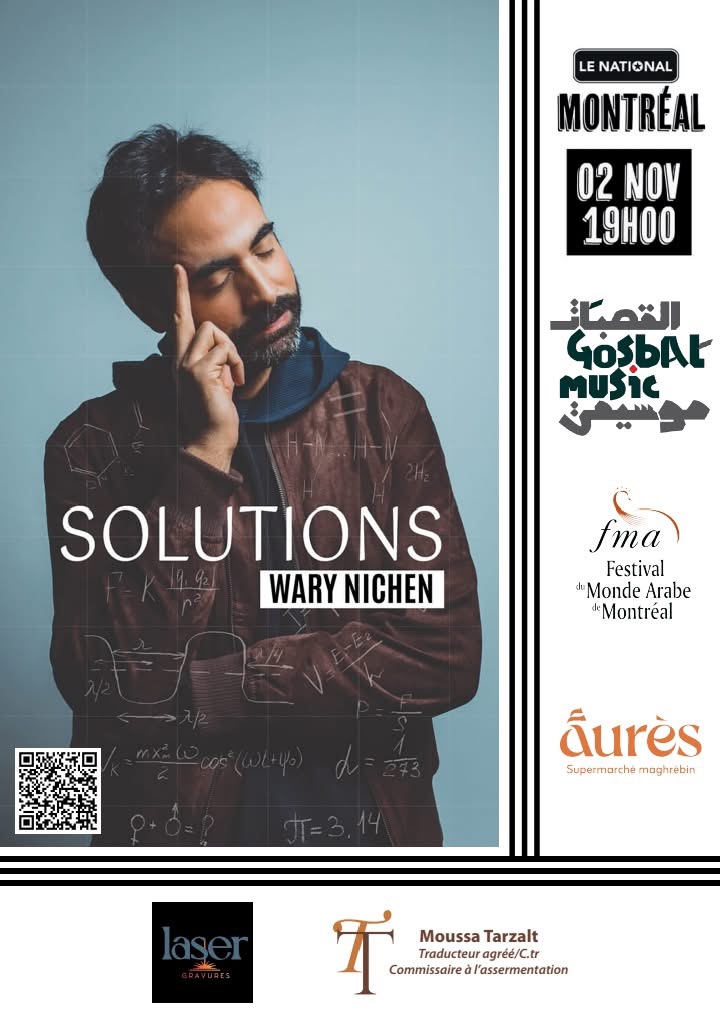

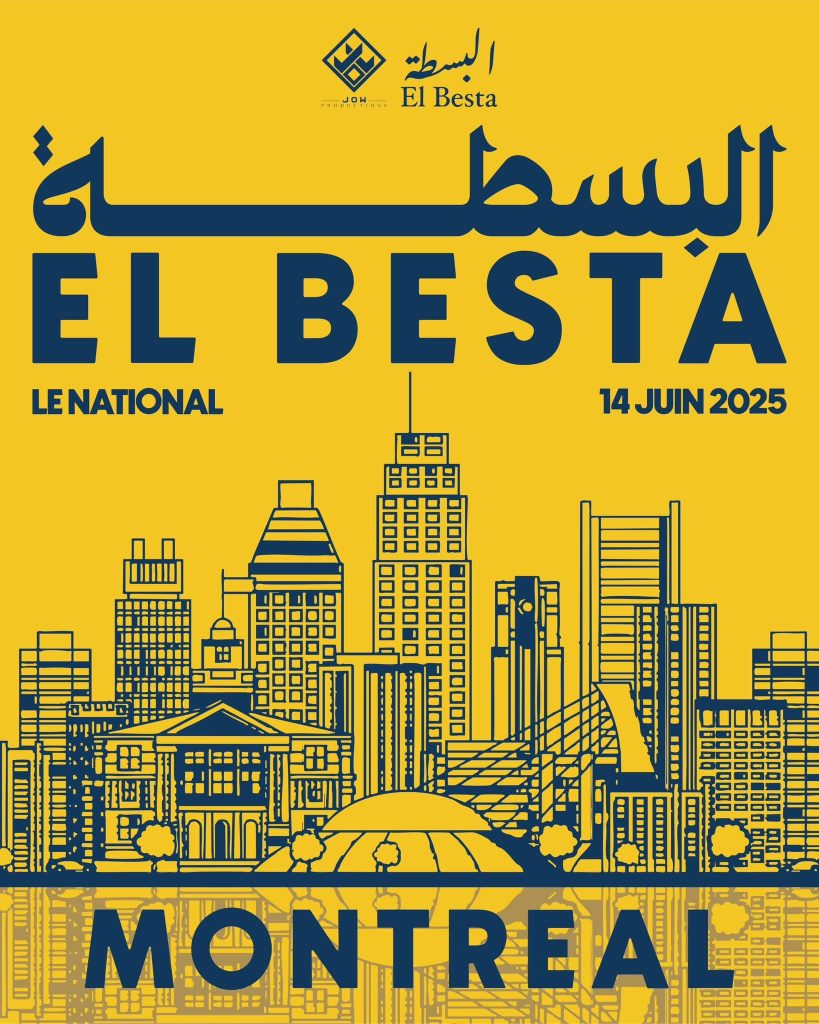

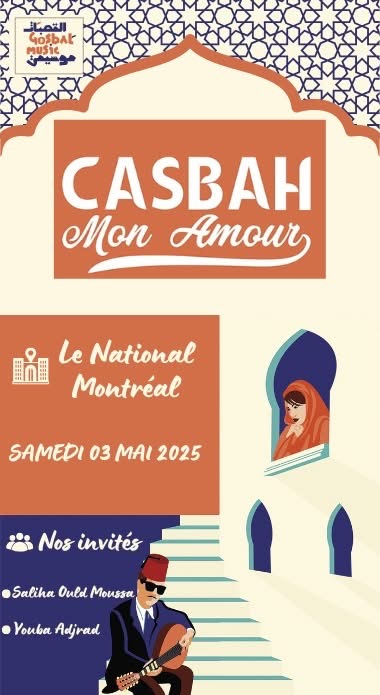

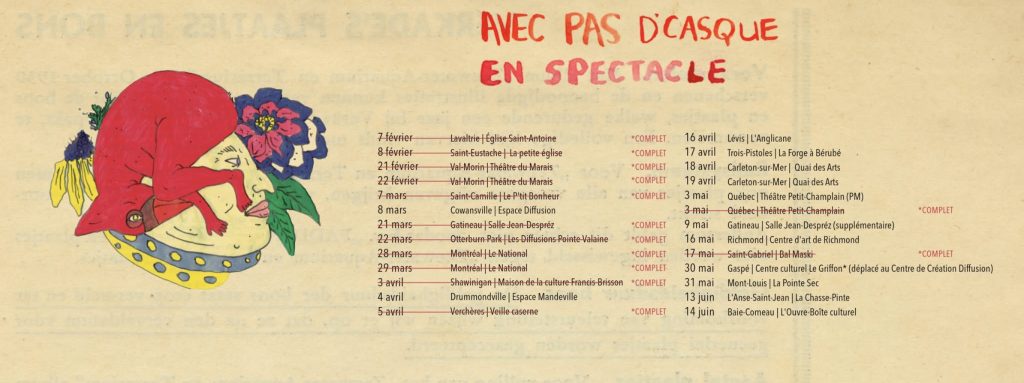

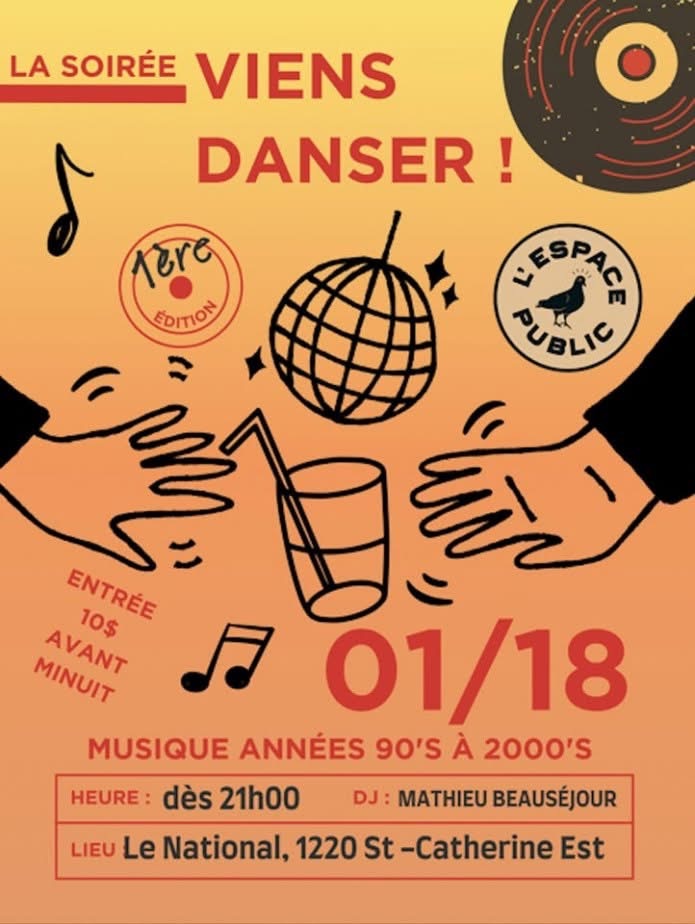

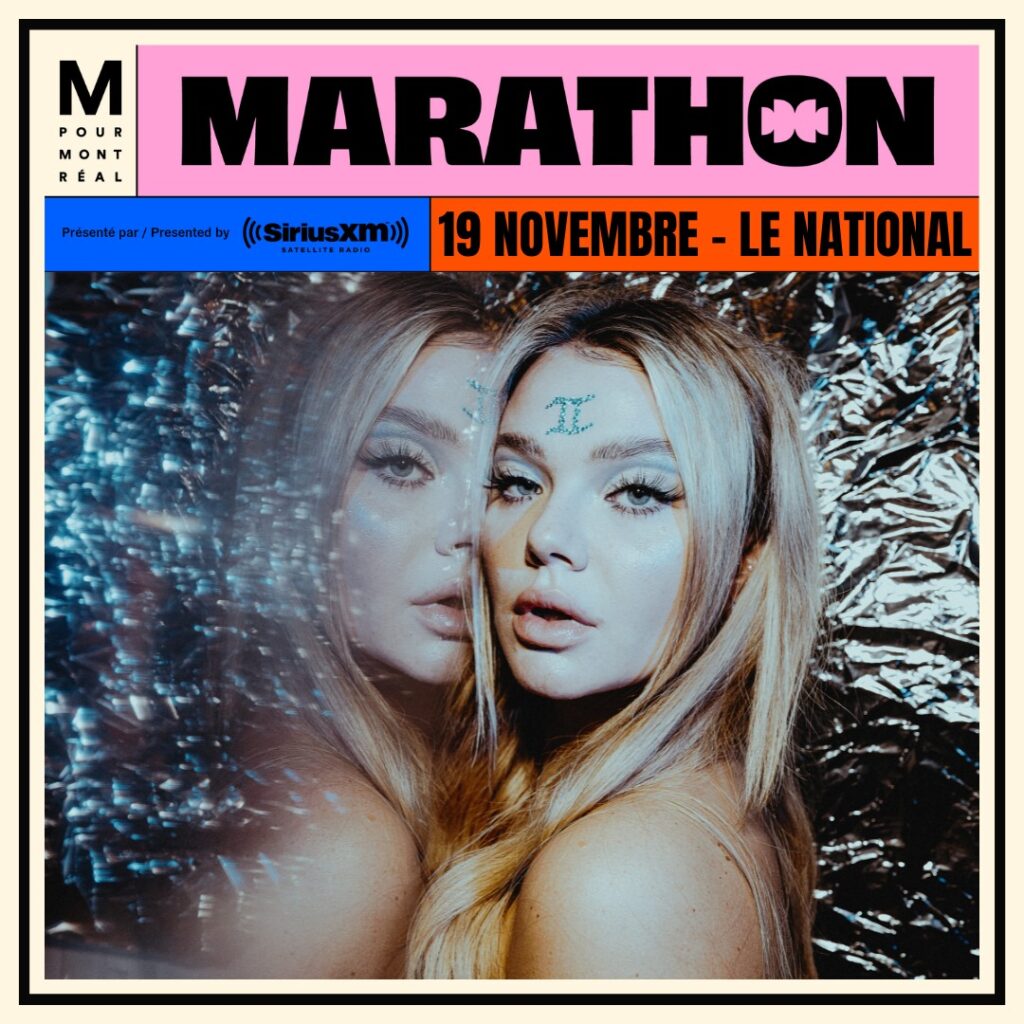

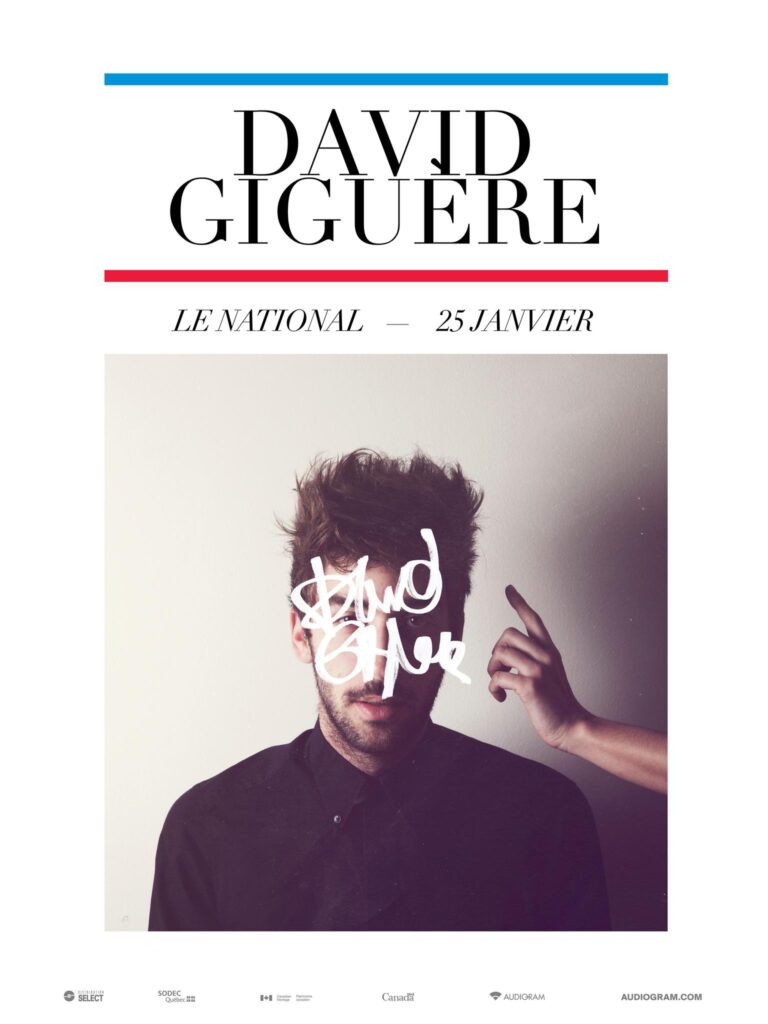

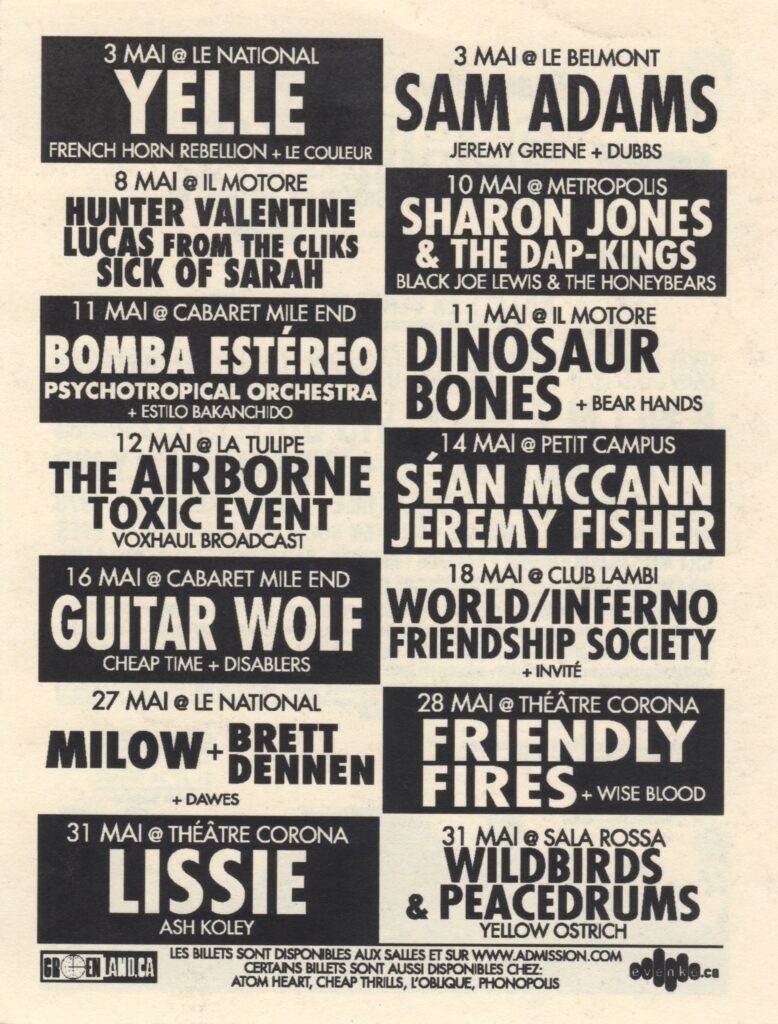

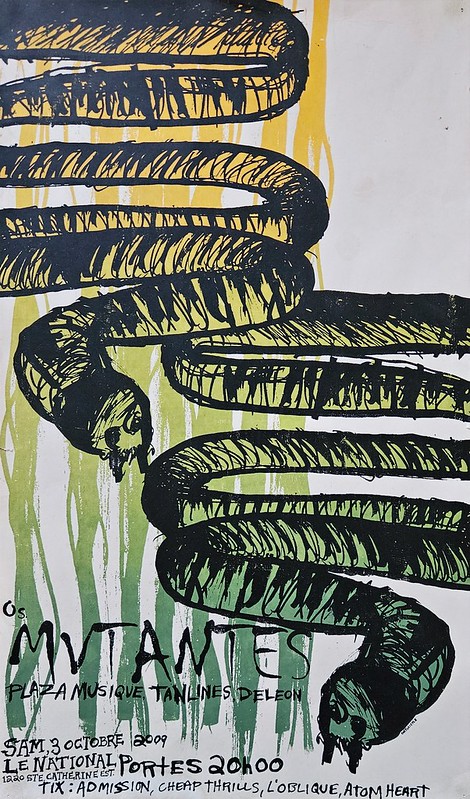

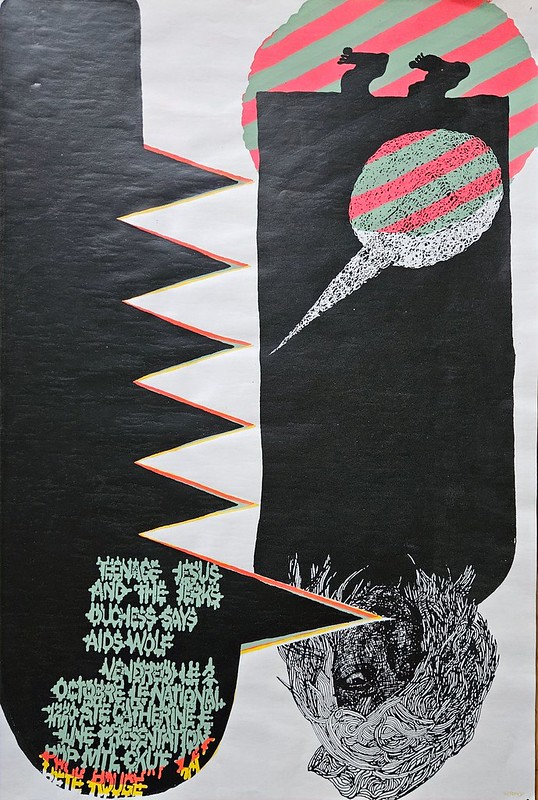

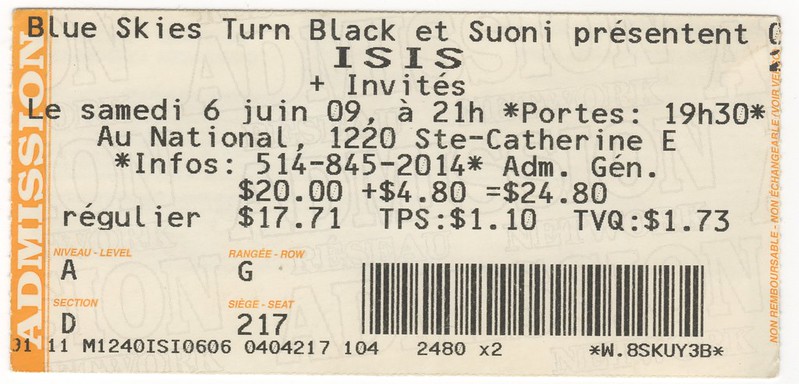

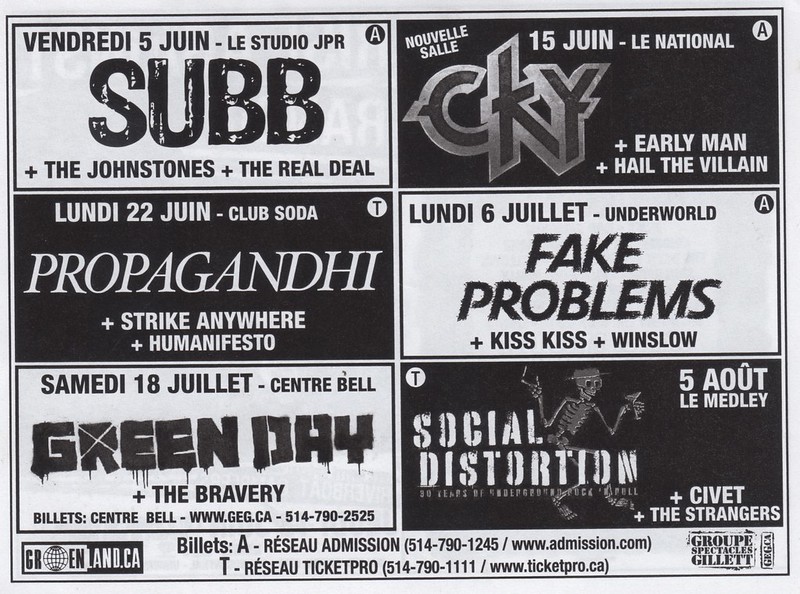

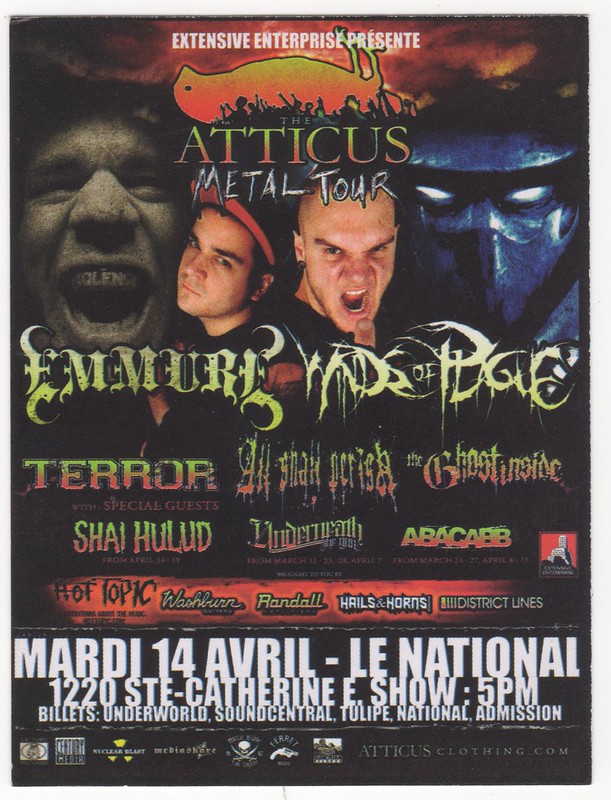

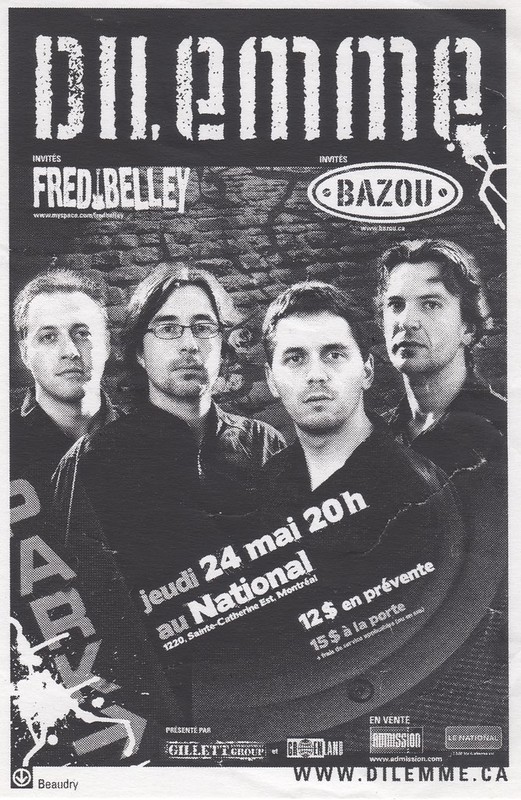

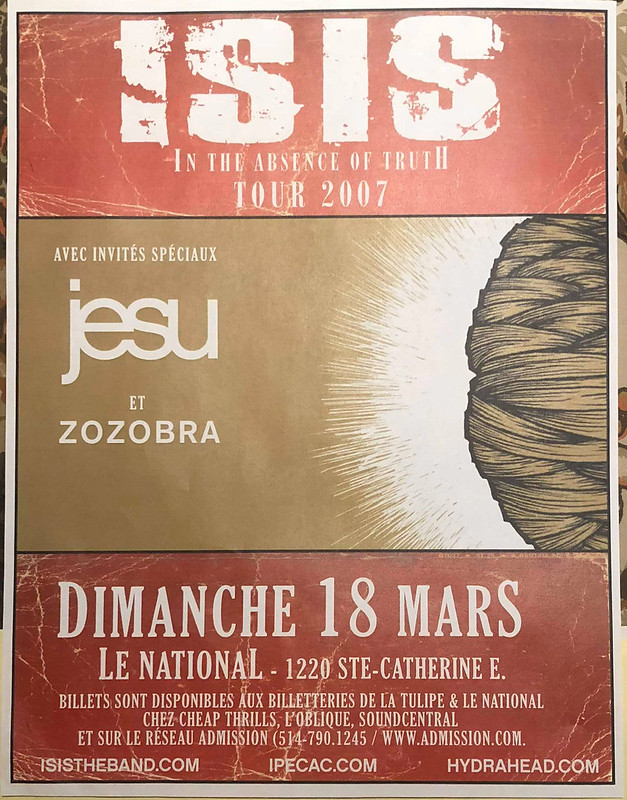

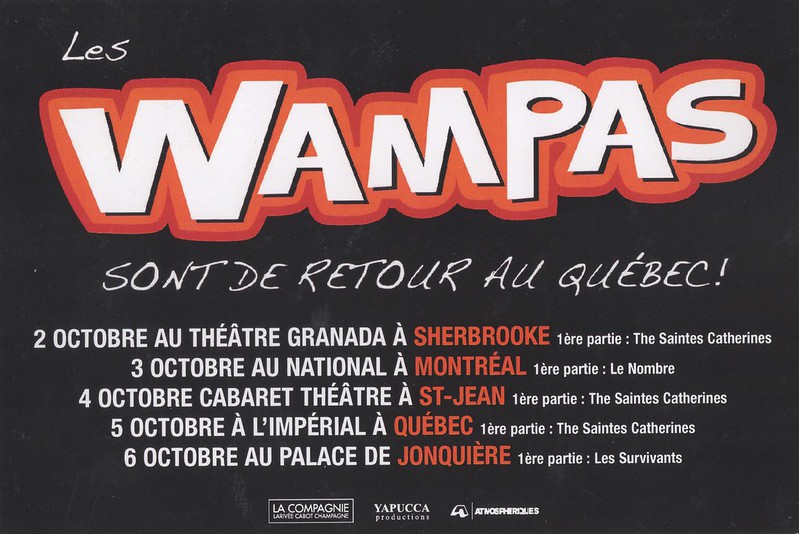

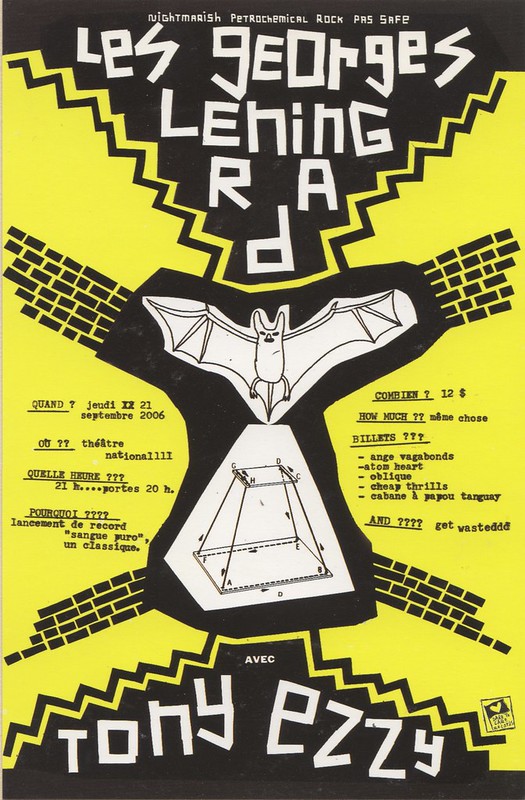

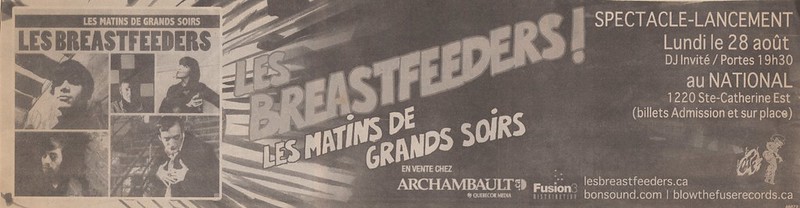

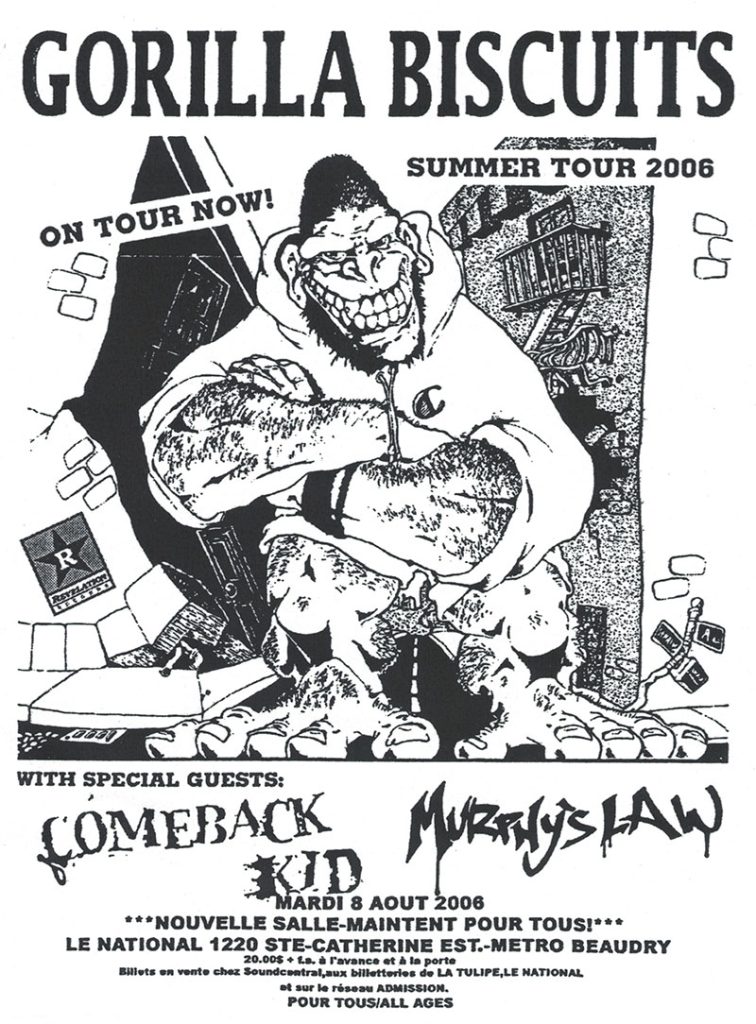

In 2006, the venue was refreshed in record time by Larivée, Cabot, Champagne and renamed Le National: paint, benches, sound system, lighting, dressing rooms — while preserving an old-time atmosphere. Since then it has hosted a wide range of artists (from Robert Charlebois to Vampire Weekend, Caribou, Simple Plan, Half Moon Run, etc.) and the TV show Belle et Bum (since 2011). [4], [6]

14. Quick timeline

- Aug. 12, 1900 — Inauguration of the Théâtre National Français (Sincennes & Courval; 670 seats). [1]

- Sept. 4, 1900 — Official reopening under Georges Gauvreau. [1]

- Mar. 1901 — Paul Cazeneuve becomes artistic director; intensive weekly programming. [10]

- 1901–1903 — “Moving pictures” during intermissions; growing integration into programming. [10]

- 1900–1910 — Weekly pace; stable troupe (“pensions”); strict discipline. [10]

- 1915 — La création du monde: projected scenery (Daoust). [10]

- 1918–1923 — Paul Gury: moral theatre; Le mortel baiser (1920) becomes a hit. [10]

- 1923 — Maria Chapdelaine (stage adaptation at the National). [10]

- 1920s — Shift to variety / burlesque; elite critical coverage declines. [10]

- 1936–1953 — Rose Ouellette (La Poune) era: burlesque peak. [4], [10]

- from 1934 — France-Film: burlesque + French films before shows. [10]

- 1953–1960 — Grimaldi, Radio-Cité, then new leases/tenants. [9]

- 1968–1973 — The Conservatoire d’art dramatique occupies the National. [10]

- 1984–1993 — Cinéma du Village (gay art-house → erotic). [7], [10]

- Mar. 25, 1995 — Reopening: Alys Robi show. [1], [2]

- 2000 — Centennial (historic 5@7). [3]

- 2006 — Renovation & rebrand: Le National. [4]

- since 2011 — Belle et Bum recorded at the venue. [6]

- Nov. 24, 2025 — “Mémoires du Théâtre National” exhibition (125th) + virtual exhibition. [10]

15. Owners & tenants

According to L’Annuaire théâtral, the property belonged to a French-Canadian family (1900–1949), with a real-estate lineage traceable back to 1843 (Allen Robertson → Peter McMahon → Joseph Brière). In 1949, it was transferred to Théâtre Frontenac Ltée, which honored existing leases (France-Film, 1934–1949; Ideal Tea Room, 1946–1951; various storefronts 1212–1224). In 1955: Ciné World Canadian Ltée, then 1957: Arcadie Corporation. In 1978, the building was sold to Kuo Hsiung Chu and Lin Cheung Tsui, who turned it into a Chinese cinema. [9], [10]

Notable tenants and leadership: Julien Daoust, Albert Sincennes, Georges Gauvreau, Paul Cazeneuve, Paul Gury, Olivier Gélinas, Louis-Honoré Bourdon, Joseph Cardinal, Jean-Marie Grimaldi, Yvan Dufresne, Jean Bertrand, etc. [9], [10]

16. Notes & sources

- Alan Hustak, “Curtain up on new venue, Century-old theatre comes back to life”, The Gazette, March 20, 1995.

- Jean Beaunoyer, “Le Théâtre National renaît”, La Presse, February 28, 1995.

- Francine Grimaldi, “Modeste 100e anniversaire”, La Presse, August 4, 2000.

- Émilie Côté, “Le Théâtre National reprend vie”, La Presse, February 9, 2006.

- “Le O’National ferme ses portes”, Montréal-Matin, January 12, 1977.

- Le National official website — history section (and/or “Belle et Bum” pages).

- André-Constantin Passiour, “Un village en perpétuelle transformation”, Fugues, March 26, 2024.

- “Restaurant des Deux Frères”, Théâtre National en Français, October 6, 1902.

- Denis Carrier, “Les administrateurs du Théâtre National”, L’Annuaire Théâtral, Fall 1988 – Spring 1989.

- Ève-Catherine Champoux, Mémoires du Théâtre National (virtual exhibition / 125th commemoration of the Théâtre National), thematic pages “Le premier âge d’or”, “Le cinéma”, “Le second âge d’or : le burlesque”, “Le conservatoire (1968–1973)” and “À propos”, 2025 (official site). Source: https://theatrenational125ans.ca/s/expo/page/a-propos